BY: MERRY JONES

BY: MERRY JONES

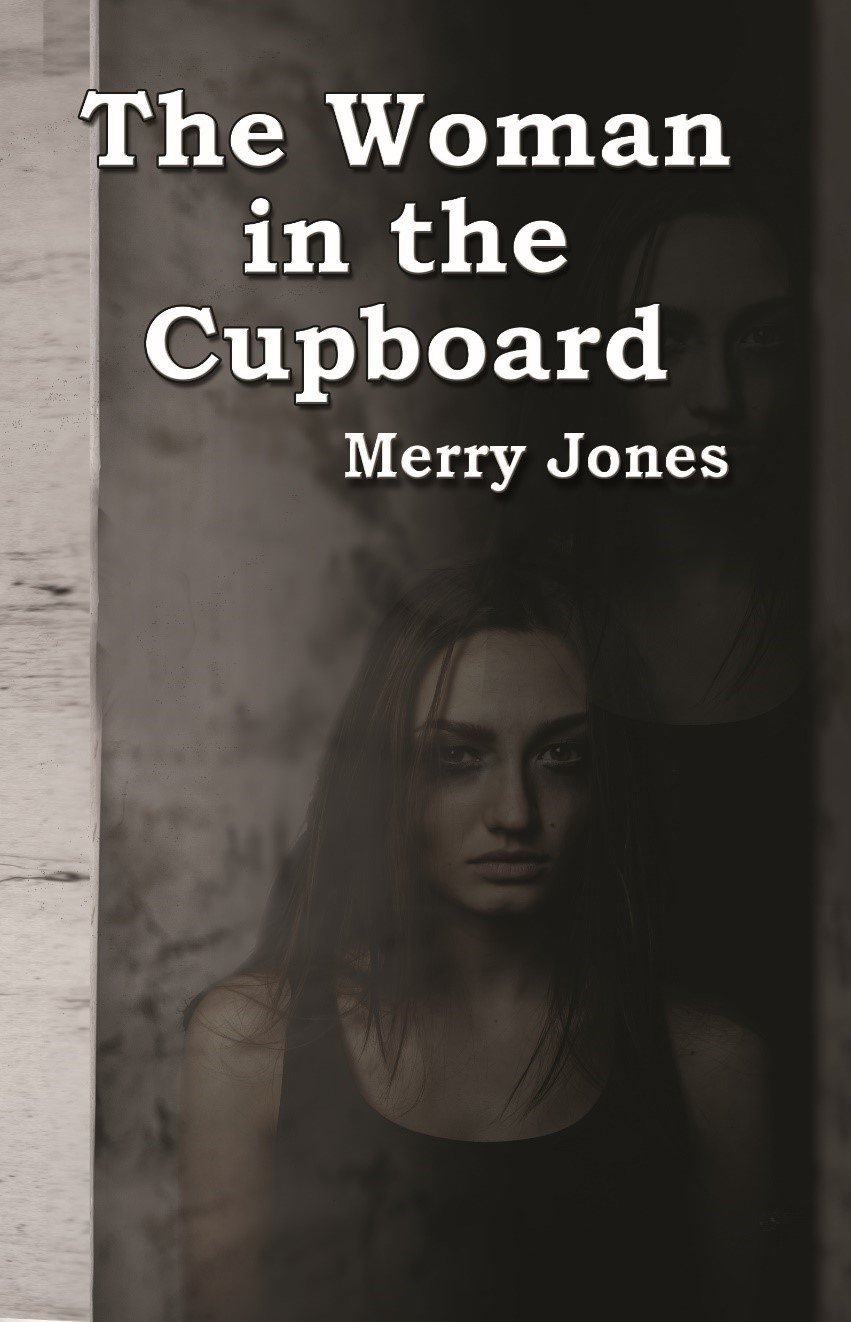

Vanessa isn’t her real name. Nobody knows what is or where she came from. All they know is that the Woman in the Cupboard was found at the scene of a grisly double murder. And that she doesn’t speak.

Detective Mo Sterling and her partner, D’Angelo, set out to solve the homicide cases—the murders of prominent Philadelphians Mr. and Mrs. Dixon Granger, and the investigation leads them into dark and unknown territory, a subculture of secrecy, power, potions, poisons, and dark passions. As the woman called Vanessa regains both her ability to speak and her memory, she recalls not only who killed the Grangers, but also the vicious crime that ripped her from her island home and forced her to be a servant in their kitchen. The investigation traps the detectives in a near-lethal web of drugs, deceit, and human trafficking, while Vanessa faces a dilemma. Should she help rescue the detectives and once more risk losing her own freedom? Or should she flee, avenge the wrongs done to her, and reclaim the life she should have had?

PROLOGUE

December, 2018

The slash comes from nowhere. Fast, unexpected. At first, the old woman cannot understand why blood is spraying from her, shooting in thick spurts. She clutches her throat, feels the thick warm eruption, sees it spattering her shelves, her carefully preserved vials and jars. She stumbles against the wall, struggling to stay on her feet, wondering how she’ll clean it all up. Where is her son? Why isn’t he helping her? She strains to call out his name but can make no sound. Careful to not to slip in dark puddles, she staggers the few steps from the kitchen to his bedroom. He will get help. He will save her. She thrusts herself into the room but he doesn’t jump to her aid. He lies limp, his body drenched scarlet on his hammock, a gash in his throat, his only eye dangling from its socket.

She blinks, but the scene does not change. The old woman lets go of her wound and sinks to the floor, perhaps sensing a filmy, slender figure just out of sight. Fading, accepting defeat, she grasps what has happened.

So. She thinks, sinking into the growing darkness. She has come back.

CHAPTER 1

May, 2018

I took the call first thing Monday morning, before I’d even taken a bite of my jelly donut.

“Already?” D’Angelo sighed. He looked tired, the bags under his eyes darker than usual, but he stood, wrapped a napkin around a couple of donuts and grabbed his coffee.

Neither of us talked in the elevator. It was, after all, Monday, and neither of us was happy about being awake, let alone at work.

I drove, mostly so D’ could eat.

“So, what is it?” His mouth was full, the sugar bringing him to life.

“A double. Apparently pretty bloody.”

D’Angelo swallowed. His eyes popped. “Wait, what? You’re saying there are two vics?”

“Yes, two. What else would ‘double’ mean?”

“Mother of God.” D’Angelo shook his head and swallowed. “Unbelievable.”

What was unbelievable about a double homicide? I pulled out of the Roundhouse parking lot.

D’ watched me, clutching his donuts and coffee. “You won’t believe this, Mo. Last night, Teresa woke me up, scared from a nightmare. She dreamed I was twins.”

“Two of you? That is a nightmare.”

D’Angelo was always going on about his wife and her dreams, as if they had some kind of meaning. I made a left, hoped Vine Street wouldn’t be backed up.

“No, listen. My twin and me—Teresa said both of us were wandering around covered in blood. How do you explain that, Mo? She has that dream and, Bam, the very next morning, we get the call about two blood-soaked victims.” He was convinced that her dream had been a premonition.

I told him that his wife was always having crazy dreams and that he was looking for connections where none existed. I said what I always said, that dreams were just our brains firing random messages, sorting themselves out. But D’ kept repeating that the dream foretold trouble, that he had a bad feeling about this call.

“Mo, it’s no coincidence. We get a double homicide right after she dreamed I was twins? If that’s not a premonition, what do you call it?” He took a sip of his coffee.

“I call it Monday morning.” I drove through a red light. “Besides, if you were covered in blood, you wouldn’t be wandering. You’d be flat on your back.” D’Angelo didn’t do well around blood, had been known to pass out at grisly crime scenes. He was a burly bear of a man, fifty-two years old. Had been in homicide for decades and seen it all, but when massive quantities of blood were involved, he took a dive.

“That’s a vasovagal response, Mo. It’s neurological. Nothing I can do about it.”

“I’m just saying. Either the guys in her dream aren’t you or they’re not bloody. Forget about it.”

I swerved past a guy who was straddling two lanes. D’s coffee splashed. He scowled, holding it high as if that would stop it from spilling. “Jesus, Mo.”

I ignored him, pulled onto the Vine Street Expressway, which was jammed. Damn.

“Siren? What do you think?”

“Sure. Won’t do much good, though.”

I turned on the flashing light and siren, but the cars around us had no place to go. I nudged them over to the right, one by one, inching ahead, cursing my decision. I should have taken Arch Street, even Market.

D’ talked over the siren. “Teresa said the dream was a sign that something bad’s coming my way. She wanted me to call in sick.” He stared at his sloshing coffee, bounced a leg.

“Relax, would you?” Teresa’s cataclysmic dreams popped up every few weeks. Probably linked to her hormones, maybe change of life. “Seriously. Let it go.”

“So, you’re saying she’s wrong?”

“No, she’s right. Something bad is going to happen. Something bad always happens. D’, we work in homicide.”

“Mo. I’m serious—”

“D’. You do this every time Teresa has a dream.”

“I don’t—”

“You do.” I started listing them, the dreams I could recall. Dreams of kidnappings, train wrecks. Of people being tossed out of skyscraper windows. Of arson and mayhem.

D’Angelo finally quieted down. But I could tell he was still contemplating the dream because his leg kept bouncing, and he didn’t say another word the whole way to the crime scene.

CHAPTER 2

The report was that the scene was gruesome. Not that it mattered. I wasn’t like D’Angelo, didn’t swoon at violence and gore. What killers did to their victims didn’t affect me much. No matter how grisly the crime or sympathetic the victim, I regarded scenes without emotion, in a state of objective detachment. I clicked into “detective” mode, switching gears, shutting off my feelings, seeing only evidence.

D’ thought my attitude was unhealthy. “You’re gonna get cancer, Mo, you keep bottling up your feelings. All that anger and revulsion builds up. It’ll sit inside you and fester and balloon until it bursts and makes you sick.”

Maybe he was right. But it didn’t matter. As a female in the Philadelphia Police Department, my career demanded that I be tougher and calmer, steadier than my male counterparts. I approached that new double homicide in my usual way, by shifting from Mo Sterling the woman to Detective Sterling the cop. I straightened my shoulders, set my jaw, numbed my emotions, and headed into the study of the elegant old house off Rittenhouse Square.

The 911 had come from a guy named Timothy Saunders, a paralegal working for the homeowner. He’d shown up to accompany his boss to a meeting in New York, used his key when no one answered the door. When D’ and I got past the crime scene tape and gaggle of uniforms surrounding the house, we found him cowering on the front steps with a not much steadier Tom Reynolds, the first cop on the scene. Saunders was bug-eyed, his skin sallow. He hugged his briefcase against his belly. D’Angelo charged inside toward the crime scene. I stopped to introduce myself and ask Saunders if he’d be okay for a few minutes. Then I followed D’ and Reynolds into the house.

The foyer was domed, marble-floored, topped with a multi-tiered crystal chandelier. Reynolds led us to the bottom of a majestic winding staircase. “It’s on the left. Second room.” He pointed the way.

We passed a set of carved double doors leading to the first room. I glanced in, saw a living room—or did the rich call it a parlor? A sitting room? Whatever, it was beige—everything was beige. Sofas, love seats, walls. Even the rugs were in tones of pale neutral brown. The only color came from a monster green plant and a huge painting over the mantelpiece—something abstract, smears of red, yellow and purple.

Even with booties covering them, our shoes clacked on the marble. A long smear of red led from the second room to a doorway up the hall. Drag marks? An aborted clean up attempt? Maybe both? As always, D’Angelo walked too fast for me. At six foot two, he was eight inches taller than I was, his legs longer. I’d have to jog if I wanted to keep pace, but if I did, he’d only speed up to stay ahead. As usual, he got there first, went in first.

And came out looking green.

I put a hand on his shoulder, and went on in. Recognized the fresh stench of death. Took in the scene while D’Angelo hung back behind me.

Dixon Granger, aged 61, high profile attorney and philanthropist, sprawled on an Oriental carpet, almost decapitated. His suit jacket was folded and draped over the back of a leather sofa, his necktie on top of it. Granger’s head dangled at an impossible angle from his body, his eyes peering through not quite closed lids. The cut on his neck was clean, exposing tissue and bone. The blood on his body was so thick that it had caked, cracking like rivers of dried red lava. The carpet was stained but not drenched the way the body was. The murder had likely occurred elsewhere.

The other victim was Judith Granger, aged 54, art collector, Philadelphia socialite, and charity fundraiser. She had been hacked in the face so severely that it would be necessary to use fingerprints or dental records to confirm her identity. She’d died wearing an ivory silk robe, now soaked with crimson. Her arms and hands were striped with defensive wounds. Matching slippers had slid off her feet and lay abandoned on the carpet. A blade had entered and exited an eye socket. Probably that was the lethal wound.

Not that it mattered.

Judith Granger’s body still wore diamond earrings, a jumble of gem-studded bracelets, a roped gold necklace, a mammoth diamond ring set. Dixon wore a signet ring and a heavy gold watch.

A small fortune in jewelry, not stolen.

The study was chilly. I shivered, looked away from the bodies to the walls of bookshelves, the mahogany partners desk. The paintings of hunting dogs. The crystal bottles on the bar along the far wall. The crimson drapes, closed around the windows. CNN playing on the big screen television. The spilled glass of what smelled like bourbon on the coffee table.

“Looks familiar, doesn’t it?” D’Angelo hefted his pants up, looked at the walls, the ceiling, the door. Anything but the bodies. “It’s just like the others.”

In fact, the murders resembled two of our open cases. Sylvia Blake had been a secretary at Dixon Granger’s law firm, a divorcee who’d lived in a nearby luxury condo. She’d been stabbed to death nine days earlier. And just days before that, J. Steven Richards, one of Dixon Granger’s law partners, had been found in his Porsche with his throat slit.

“Let’s look into the relationships,” I said. “See if they’re connected.”

“If? Obviously they’re connected. All of them were stabbed. Three of the vics worked together. And all four were killed within—what? Two blocks of each other? They’re connected, Mo. It’s the same guy.”

D’Angelo was probably right. But as always, he was ahead of himself, making assumptions. And as always, I pulled him back. “Before you close the case, Sherlock, we ought to find out a little more.”

D’ harrumphed. “It’s one guy. You know it as well as I do, Mo.”

“I don’t know anything yet.”

He shook his head. “You wouldn’t know the nose on your face unless we tested it for DNA.”

I smiled. “But I would know your ass, which is where your head should be.”

“Okay.” D’ smirked, as he put a hand up. “But you’ll admit it sooner or later. The same guy did them all.”

I didn’t answer. Didn’t have to. We both knew that we had to do the legwork. Look into the relationships between Granger and Blake, Blake and Richards, Richards and the Grangers. We had to find out who had reason to kill them, who might benefit from their deaths. And we had to see what the techs pulled in—the killer might have left blood or prints.

About then, Franks arrived with the medical examiner’s team, and D’Angelo went to catch up with crime scene techs and take a statement from poor Timothy Saunders. I stepped out of the ME’s way but stayed close, studying the wounds. Estimating the strength and rage it would take to inflict them. What had driven that amount of rage? I imagined being the killer, seeing from his eyes, his mind. Obviously, I’d have killed Dixon first, eliminating the larger, stronger victim. And because Dixon had no defensive wounds, I must have struck him suddenly, surprising him, not giving him time to respond. My weapon would have been sturdy yet sharp as a scalpel. And I’d have struck with not just force but also precision, the first blow accurate enough to halfway detach his head.

Unlike her husband, Judith Granger had many wounds, so I couldn’t tell which had been intended, which had occurred in a frantic struggle. But clearly, Mrs. Granger had fought. She lay on her back on the Oriental carpet, one knee bent and one arm extended over her head as if she’d been doing the backstroke, trying to swim away. Again, I pictured myself as the killer, chasing after her, pouncing onto her as she crawled across the rug, rolling her over, fighting her, stabbing and slashing until my arm ached, until blood spatter blinded me.

“Mo,” D’Angelo called from the doorway, gestured for me to join him. “Let’s move.”

He was always rushing.

“There’s stuff you need to see.”

Franks looked up from Dixon Granger’s body. “Go on, Mo. We got this.”

Reynolds stood at the study door like a palace guard. As I stepped past him, D’ started walking, talking to me over his shoulder. “I sent the paralegal home. He doesn’t know squat.”

Really? How could D’ be so sure? “D’, he must know something. Saunders worked with three of the vics, and he has his own house key.”

“The key doesn’t mean anything. He just used it to pick things up for his boss.” D’Angelo led me along a trail of dried blood down the hall, into a vast kitchen of white tiles and stainless steel. “Granger often traveled at the last minute, needed a suitcase. Or he worked at home and needed files delivered. Seems like Saunders was his personal lackey. Trust me. The guy might be worth talking to later, but for now he’s a mess, better off at home.”

He stopped, pointing out the blood trail behind us, spatter on the walls, traces of wide pools on the floor. “Probably Mrs. Granger was dragged to the other room. But the action happened in here. Someone tried to clean up.” He moved on, swung a door open, revealing the laundry room. Crime scene techs were in there, collecting evidence. “This, though, is interesting.” D’Angelo nodded to one of them. “Show her, Al.”

Al lifted the lid of the washing machine, revealing a tubful of dark pink water and soaking clothes. Blood soaked?

“The load was running when Reynolds got here. He noticed it while he was checking to see if anyone else was here.”

“And he looked in the washer?” Had he thought the killer was hiding in there?

D’Angelo jingled change in his pocket. “He looked inside because he thought it odd that someone was doing the wash right after the people who lived here were killed. It’s a good thing he did. He stopped the cycle.”

I didn’t get it. I stared at the load. “So, the killer was washing his clothes here?”

D’ shrugged. “Wait. There’s more.” He guided me back into the kitchen. Another tech stooped beside the open dishwasher, pointed out a meat cleaver and a long steel carving knife. Dark brownish red matter blood clotted around the handles.

The murder weapons? I stooped to get a better look. Why had the killer left everything in the house?

“How about the rest of the place? Anything else interesting?” I stood, scanned the cabinets, the fridge.

“You and I should take a look. Reynolds and the uniforms cleared the upper levels and the basement. Upstairs, there’s a media room, bedrooms, bathrooms, an office. Downstairs, they’ve got one of those infinity pools and a sauna. A complete fitness center. Also a small cubby with a head, day bed and closet with some white dresses, size six. Looks like a maid’s room.”

“Yeah?” I stepped around him, opening cabinets, checking out plates and bowls, noting that the Grangers had about a half dozen brands of high fiber cereals. “Any sign of the maid?”

“Nope. She might not live in.”

Right. Or she might be stuffed in some closet, dead. I opened the refrigerator, saw yogurt, bags of kale, a head of broccoli. Lactose-free fat-free milk. Had the Grangers been health nuts? I thought of Dixon Granger’s beefy frame, the glass of spilled bourbon. Maybe the wife had been the health nut. Or she’d been trying to get him to eat better.

“So, let’s do a walk-through.” I shut the door, wondered if food had been a point of contention between them.

“Let’s make it fast. We need to get to the partners, find out what Granger’s been working on.” D’Angelo was already on his way out of the kitchen, as always in a rush. Wherever he was, he had someplace else to go. Bounced a knee when he sat. Jingled the coins in his pockets, fidgeted. Had to move constantly.

I didn’t rush after him. I took my time, resisting D’Angelo’s pressure. I opened a cabinet full of dishes. Another full of pots.

“Mo, nothing’s in here,” D’ said. “Let’s move.”

I ignored him, looked into the cabinet under the sink, stepped over to the pantry and opened the narrow door.

And faced a striking dark woman with large blank eyes. Wearing a white uniform, she sat on a case of canned seltzer beside a wall of shelves stocked with bottled water, paper towels, and twelve-packs of canned tuna. The other wall was bare, painted a deep sky blue.

![]()

The woman concentrates on the color before her. It reaches high and wide, and does not move. It remains steady, without sound or edges, plain flat blue.

She watches the color, and the blueness deepens, expands like a cloud and dissolves into the air where it reaches out to her face. She takes it in as if it were a breath. But she knows it is really a color: blueness.

A voice—Is it her teacher’s? M. Roger’s? Is she in school? The voice asks her name. Her name? The voice floats away, comes around again, asking again. She must respond, and so she does. But then it asks more, and more again. She reaches into the blue, trying to pluck out answers, missing some, grabbing others, not sure if they are acceptable or correct. Is it an exam? She hasn’t studied—doesn’t know how to respond. She speaks to avoid speaking, says what she cannot say. The air is heavy. Maybe she is not speaking and no one is asking. Maybe the wall isn’t blue, and there is no wall, only her own breath. Or maybe there is no breath and she is herself the air, because she is gone like a deep blue cloud, no longer alive.