BY: A. J. SIDRANSKY

BY: A. J. SIDRANSKY

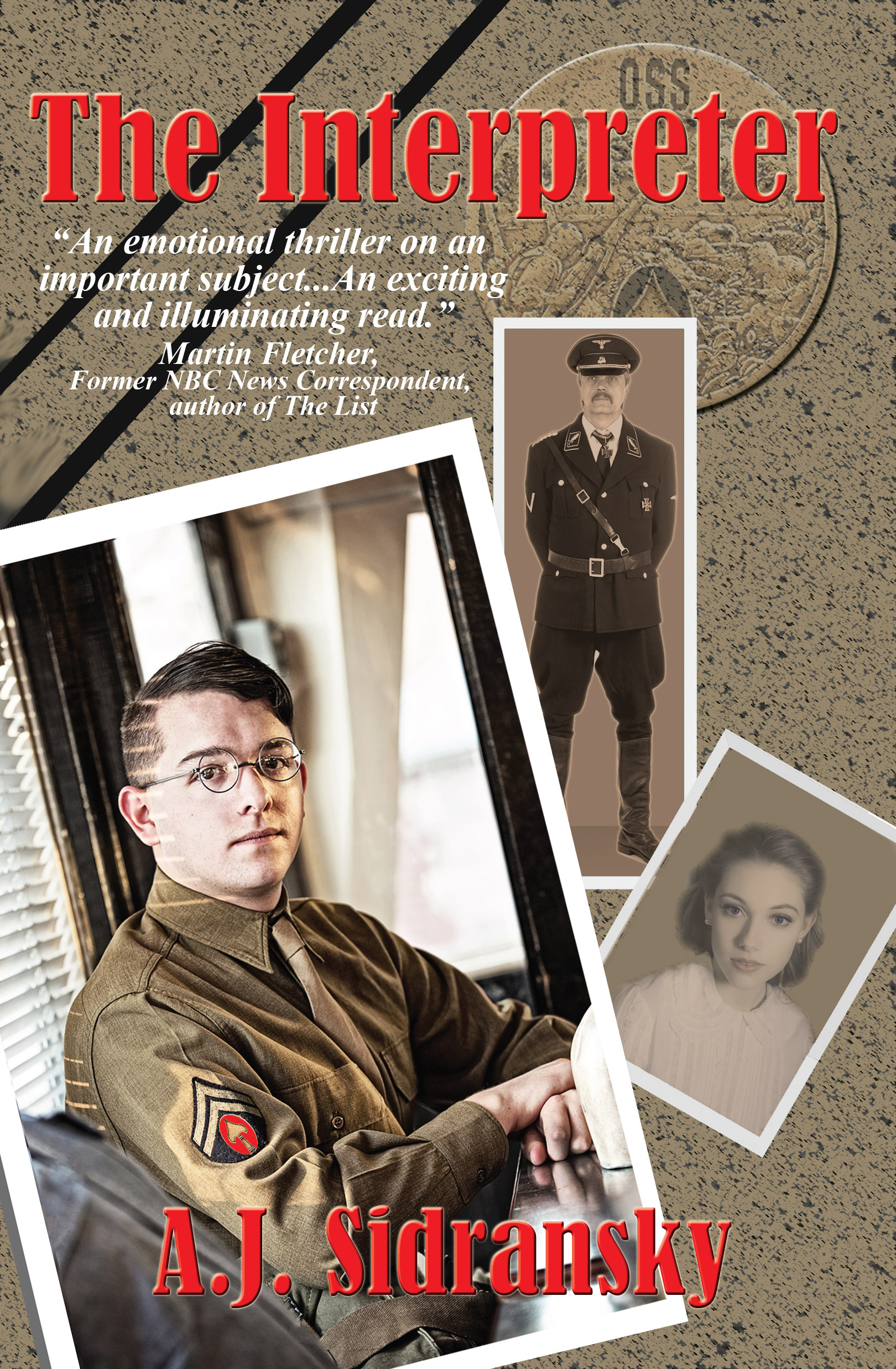

In the heat of wartime Manila, 23-year-old American GI Kurt Berlin is recruited by the OSS to return to Europe to aid in the interrogation of captured Nazis. A refugee from the Nazis himself, Berlin discovers the Nazi he’s interpreting is responsible for much of the torment and misery he endured during his escape. And that very same Nazi may hold the key to finding the girl he left behind.

Will the gravitational pull of revenge dislodge his moral compass? From the terror of pre-war Vienna to the chaos of occupied Brussels, through Kurt’s flight with his family through Nazi-Occupied France, to the destruction of post-war Europe, The Interpreter follows Kurt’s surreal escape and return. How much can a young mind absorb before it explodes?

“The Interpreter makes you feel like you’re there, in the crush of refugees fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe, carrying false papers and waiting for the SS to grab you, terrified of being recognized and wondering what you’d be willing to do to survive. The novel’s vivid prose and surreal images are reflected in today’s headlines, particularly the shameful treatment of asylum seekers on our shores and the cruel policy of separating families at the border. This novel is a powerful plea to gedenk, to remember what we lost.”

—Kenneth Wishnia, editor of Jewish Noir, author of The Fifth Servant

“Sidransky has written a powerful story about the ravages of war, a tale of love and loss, of hate and revenge and the struggle to hold onto one’s humanity in an inhumane world.”

—Jeff Markowitz, author of Death and White Diamonds

“A gripping thriller with stunning twists, The Interpreter is also history and the cure for any number of lies about the Holocaust.”

—Albert Tucher, author of The Same Mistake Twice and The Honorary Jersey Girl

CHAPTER 1

Manila, The Philippines – March 1945

Kurt’s eyes opened tentatively. He’d slept without dreaming for the first time in days of the corpse of the Japanese soldier he’d killed a week earlier on Manila’s Baywalk. The body of the soldier, no older than himself, danced like a rag doll as Kurt’s machine gun mowed him down. He was never prepared for how the act of taking another man’s life would change him.

Kurt stood and stretched, dead tired and dead hungry. The heat was intense inside the musty, improvised barracks located in an old school behind a church. He grabbed a towel from atop his duffel and wiped the sweat from the back of his neck, head, and face. Regulations required helmets be worn at all times when outdoors and in all unsecured areas. Kurt slipped it on then took it off just as quickly, leaving the barracks bareheaded. He’d take his chances.

Blaring sunshine blinded him. As Kurt’s eyes adjusted, two of his buddies waved at him from the shade of a dusty, scraggly, tree. “Where you going?” one called out.

“Mess.”

“Yeah, that’s what it is,” the other shouted back.

Kurt didn’t care how bad the food might be, he hadn’t eaten in over a day. He needed something warm in his stomach. Three men approached him at a brisk pace. Two of whom, one short and one tall, he didn’t recognize. It was clear neither had seen battle, their uniforms pressed and spotless. The third, his captain, called out to him. “Berlin.”

Kurt stopped and saluted.

“Come with us,” his Captain ordered.

Kurt’s instinct was to ask why, but this was the U.S. Army, so he just followed, his stomach grumbling.

“You were born in Vienna, Corporal?” the short one asked.

“Yes,” Kurt replied. “I believe that’s in my file.”

“No need to be a wiseass,” his Captain said.

“Sorry, sir.” Kurt suppressed a smirk. “Yes, I was born in Vienna…sir.”

“No one would know it by your English. You sound like you were born and raised in Vienna, Virginia.”

Kurt permitted himself a satisfied smile.

“I suppose your German is perfect too,” the tall one said.

“Yes, sir.” Kurt hadn’t spoken a word of German in years. After arriving in the United States, he quickly perfected the English he had been studying since he was twelve. Within a few months, Kurt refused to speak German at all. The Nazis had made it abundantly clear. Kurt may have been born in Austria, but he wasn’t Austrian, and he certainly wasn’t welcome there. “To be truthful sir, I don’t speak German with anyone anymore.”

“But you can still speak it?”

“I suppose,” Kurt replied. He relaxed a bit, letting his shoulders drop. He wondered where all this was going. “I often dream in it.”

“Good,” the tall one replied, this time in German. Kurt was surprised. The officer’s English was as natural as his own. “My name is Captain Johan Rosenthaller, and this is Major Eric Winston. I was born in Germany, and I am also Jewish.” He had the thick, formal accent typical of Berliners.

“How do you know I’m Jewish?” Kurt interrupted in English.

“It’s in your file, corporal.” Rosenthaller continued in German. “We would like to offer you the opportunity to do something unique for your new country.”

“And that has something to do with my ability to speak German?” Kurt replied, again in English. He wasn’t going to give Rosenthaller the satisfaction of hearing him speak German.

“Yes.”

“If it requires me to speak German, I’m not interested.”

Rosenthaller looked at Kurt’s commanding officer. “Perhaps, we’re done here.”

“Berlin,” the Captain said, “hear the man out.”

Kurt, tired and hungry, figured the quickest way to a meal was to hear what Rosenthaller had to say. He leaned back in the chair, purposefully disrespectful of Rosenthaller’s rank. “Okay, what do you have in mind?”

“We represent United States Army Intelligence. We’ve captured a lot of Nazi officers, Wehrmacht, SS, Gestapo. We need native German speakers as interpreters. Men like yourself, who understand the nuance and subtext of what these bastards are and aren’t telling us.”

Kurt’s mind raced. He never wanted to hear a word of German or see the decaying grayness of Europe again. It held nothing for him save sorrow and loss. At the same time, a single face appeared before his eyes.

“You would be promoted to Lieutenant,” Winston said.

Kurt’s mind continued to float. He was somewhere else, so far away he could feel the cold tingle of a European winter on his skin even as sweat dripped from his scalp.

“Corporal Berlin are you interested?” Rosenthaller asked, this time in English, breaking the spell of Kurt’s memories. Rosenthaller switched again to German, knowing full well that only he and Kurt would understand. “It’s not only a strike for your adopted country, it’s a strike for our people, for the millions who have disappeared.”

Rosenthaller’s voice and words gained volume and clarity in Kurt’s mind.

“Where would I be stationed?”

“Brussels”

Kurt’s decision was made. “When do we leave?”

“1500.”

![]()

Brussels looked like a bruised boxer, though badly beaten up one could recognize its face. The streets, once orderly and clean, were dirty and filled with the detritus of war. There were rubble-filled gaps between the buildings and pockmarks from gunfire everywhere.

Kurt was both happy about, and dreaded, being in Brussels. It was his ground zero, the intersection where his past, present, and future collided. Brussels held the answers to Kurt’s most piercing questions, whether those answers would be miraculous or disastrous.

The first few interrogations Kurt interpreted were perfunctory, mostly lower rank Wehrmacht officers. Often not much older than he, these men were promoted to their ranks toward the end of the war. Hitler and his generals had run out of experienced officers. They had sacrificed most of a generation, perhaps a generation and a half. These men knew little about what their superiors had done or to where they had fled to. They just wanted to go home to their families, if they still had families. Kurt detached himself from his emotions, focusing instead on translation, and the nuances of the language. He found the work more challenging than he had imagined. Rosenthaller told him the interrogators were impressed by him.

The reports and pictures from the camps were both frightening and numbing. Every time Kurt read them or looked at them, he knew he could well have ended up there, more likely dead than alive. His thoughts would drift to all the missing. Kurt began looking for his friend Saul and the Mandelbaums a few days after arriving but found no trace of them. He continued searching for information through the Army and aid organizations, walking the streets on his off hours in the hope he would stumble upon someone, anyone.

And Elsa? The day after he arrived, Kurt went to the convent where he had left her the day after he arrived, but the convent was gone. It had taken a direct hit from something: bombs, tanks, grenades, who knew. Kurt was torn. He had to find Elsa, the pain of having left her was still searing. Kurt had promised Elsa he would come back for her. Perhaps it was too late. He didn’t know if he could face the truth when he found it. Every day he planned to visit the churches to find out what had happened to the little convent. Every day he put it off until the next. Not knowing kept hope alive.

At his desk in his small, cramped office, Kurt pulled out the transcript of the interrogation from the day before. There were two copies, one in English and one in German. Typists worked all night transcribing them. Kurt had to compare them line by line to make sure the translation was correct.

There was very little of substance. The captured soldier was a Lieutenant in the Wehrmacht, stationed in Antwerp. His commanding officer died in the battle that liberated that city. The OSS wanted information on Belgian collaborators. The captured Lieutenant claimed to know nothing, his superior maintained all contact with De Vlag and the Flemish National Union, himself. The interrogator didn’t believe him, but there was no way to force the soldier to talk. They doubted he could supply any useful information anyway, so he was sent to a holding facility near the Dutch border.

Kurt peered out the window at the trees lining the street. The emerald brilliance of the young leaves was the same color as Elsa’s eyes. Spring reminded him of Elsa, it was when they had met. Kurt had to find her. The ringing phone broke his concentration. “Berlin,” he said.

“Kurt, come to my office,” Rosenthaller commanded.

“Yes, sir. Be right there.”

Kurt walked down the hall. The secretary sent him in directly. Rosenthaller sat behind his desk. Another man, in civilian clothes, stood by the window sucking on a pipe. Kurt saluted.

“At ease Lieutenant, please sit down. May I introduce Colonel Anderson McClain?”

The tall, thin, middle-aged man in a well-made, dark-grey suit turned from the window and nodded in Kurt’s direction. He dragged on his pipe and let out a cloud of smoke. The scent of the tobacco reminded Kurt of his father. Kurt rose to offer his hand, but McClain turned back toward the window.

“The Colonel arrived yesterday from Washington. He’s here on an important and sensitive mission.”

McClain turned again toward Kurt and smiled. “How old are you, young man?” he said.

“Twenty-three, last month, sir.”

“And I understand you were born in Vienna.”

“Yes, sir.”

“May I ask you a question?”

“Yes, sir. Of course.”

“In your view, what is the greatest danger facing the United States today?”

Kurt hesitated. “I’m not sure what you mean, sir?”

McClain walked around Rosenthaller’s desk and sat down. “You’re young, Lieutenant Berlin, but from what we can tell you’re very bright, or so Captain Rosenthaller tells me. Think about the past quarter century. What force has represented the greatest threat to our way of life?”

Kurt glanced at Rosenthaller. His face was a blank. “I’m sorry sir, perhaps I misunderstood your question.”

McClain smiled. “I didn’t expect an answer. Mostly, I was noting how you would respond, if you would remain calm and impartial. We need that for this project. You passed with flying colors.”

Kurt wasn’t sure what McClain was getting at. He had acted respectfully, as his parents had taught him. That’s all.

McClain leaned on the edge of Rosenthaller’s desk. He drew on this pipe and sent another cloud of smoke into the room. “Would you like the answer?”

“Yes.”

“Communism. The Soviets are the biggest threat to our future and always have been. Even more than Hitler was.”

Kurt was taken aback but maintained his composure. Nothing was worse than Hitler and the Nazis. He knew that firsthand. “But the Soviets are our allies, sir.”

“They’ve been our allies out of common cause,” McClain replied. “Their system is contradictory to ours. The war is not over, only this part. The next phase is about to begin. Fascism, in many ways, served us well. It acted as a buffer against communism and the ability of the Soviet Union to export revolution. Remember, it stopped communist expansion in Germany, Hungary, and Austria in the ‘20’s.” McClain gestured to the window. “Had Hitler stayed within his borders none of this would have happened. We might even have become allies. We had common cause against the Soviets.”

Kurt was shocked. How could this man think of Hitler as an ally? He searched Rosenthaller’s face for a reaction. There was none.

“Colonel McClain is forming a unit to determine which of these senior officers we’ve captured might be useful to us in the coming fight. I’ve recommended you to him as our best interpreter.”

Kurt hesitated. “Thank you, sir.” He wanted no part of this McClain, instinctively he didn’t trust him, but he didn’t want to be insubordinate either.

“Well, Berlin? Are you in or out?” Rosenthaller said.

“Whatever I can do for our country, sir.”

![]()

The late afternoon light cast a beautiful golden hue over the park across the street from Kurt’s office. Kurt sat down on a bench under a broad, leafy tree. An ice cream vendor filled waffle cones at a stand across the way. Ice cream always reminded Kurt of Elsa. He remembered that first Saturday after they arrived in Brussels, in the small park near the Mandelbaums’ apartment. They had gone for a walk and shared some. Her French was so perfect. She was so perfect, in her spring dress and white gloves.

Kurt had tried to forget, especially after finding the convent destroyed. His heart broke then and there. Elsa was dead. Kurt knew it. Yet, he had to be sure. He pulled a small piece of paper from his inside pocket. The address was only a few blocks away.

The Church of our Holy Savior was reached by a long, steep flight of steps. It was much larger than the church on the little side street where Elsa used to go to feel closer to her past. The doors were open. Pews had been removed from the rear part of the church, now occupied by beds and other furniture. Children played quietly in one of the small, recessed private chapels that lined its sides. Light streamed in through stained-glass windows that soared above him. A service was underway at the front of the church in the remaining pews near the altar. The scent of incense tickled his nose.

Kurt removed his cap and walked slowly and quietly to the front. He sat down in the last pew on the last seat and waited for the service to end. The sound of the priest’s chanting comforted him in a detached way. It wouldn’t have mattered if he were in a synagogue or a church, or one of the Buddhist temples or mosques he had come across in the Philippines. Kurt didn’t believe in God anymore, but the serenity of the space eased his mind. Kurt couldn’t reconcile the idea of God with what he had seen. Images of dead children in Philippine villages and German death camps haunted him. He envied these people here in the church their faith.

A priest held up the wafer, prayed in Latin. The faithful rose from their seats and filed past, kneeling and accepting the body and blood of Christ. If only, Kurt thought, it was that easy. He recalled the great comfort Elsa took from her faith, and Mandelbaum from his. Where were they now?

The morning’s meeting with McClain and Rosenthaller weighed on him. He didn’t like McClain, and he was troubled by Rosenthaller’s lack of response to what McClain had said. McClain’s statements hadn’t surprised him. Kurt learned quickly after arriving in the United States that many Americans felt an affinity for Hitler. They didn’t give a crap what Hitler said or did with regard to the Jews. They respected his quest for orderliness and power.

When Kurt arrived in Washington D.C., and then later when he entered the army and was sent to Georgia for training, he came to understand why Americans were ambivalent about the Nazis. It was because Nazi Germany already existed in the American South, only it was the Negroes who were the Jews.

The service ended. Worshipers filed out quickly and quietly, many smiling. Salvation was theirs. The priest, a man in his fifties with graying hair, noticed Kurt in the pews and approached him.

“May I help you, monsieur?” the priest said in broken English.

“Oui,” Kurt replied. “I’m looking for someone.”

The priest smiled. “You speak French?”

“Oui,”

“May I join you?” The priest pulled up his cassock at the knees as he sat down.

“Of course,” replied Kurt.

“And you believe we can help you to find this person…,” he looked at Kurt’s insignia, but was unable to decipher his rank.

“Lieutenant…” said Kurt

“Oui…Lieutenant.”

“I am looking for a nun and a young woman. The young woman would be twenty-two.” Kurt pulled out a photograph of Elsa, grasping it tightly.

The priest looked at the photo and shook his head. “No, I’ve never seen her. Pardon, monsieur, may I ask a question?”

“Yes?”

“You’re American, yet you speak French with a German accent.”

“I was born in Vienna. I came to Brussels in 1939.”

“I see. I am Father Marcel.” The priest rubbed his hands over his thighs to clean them. “You are Jewish?”

“Yes,” Kurt replied.

“And the young woman you seek? She is also Jewish?”

“In a fashion.” Kurt smiled. “That might depend on whose definition we are using.”

The priest nodded almost imperceptibly, his expression becoming more serious. “And how is it she would be with one of our sisters?”

“When I left Brussels in October of 1940, she was living with the Sisters of Charity.”

Father Marcel averted his eyes. His response was quick. “That convent was destroyed. The Germans blew it up.”

Kurt’s stiffened. “Do you know why?”

“For hiding Jews.” The Priest continued to avoid Kurt’s gaze.

“What happened to the sisters?”

Now Father Marcel looked directly at Kurt. The pain in his eyes was evident. “They were blown up with it, along with the Jews they were hiding.”

The statement hit Kurt like a thunderbolt, his worst fears confirmed. “Did anyone escape? Survive?” Kurt asked, guilty at leaving Elsa.

“No one survived, and no one escaped, but two sisters were absent at the time of the attack,” Father Marcel said. “They were saved by providence.”

“Or luck.” Kurt rubbed his eyes. He felt exhausted. “Where are they now?”

“One died last year in Louvain during the liberation. The other is here in Brussels. She lives in a convent on the other side of the city.”

“May I see her?”

The priest hesitated. “She lives as a recluse. She rarely speaks since that day. She prays to the Virgin continuously as penance for surviving her sisters in Christ.”

“May I see her?” Kurt repeated, rising from the pew.

The priest looked up at Kurt. “I will see what I can do. Come back in a few days.”