Dita Marx, dancer/choreographer, is the Artistic Director of The Harlem Center for the Arts. She has recently hired cartoonist Jeremy Windt to teach and takes him to lunch in the Coffee Exchange. There he recognizes Cassia Warshaw. She was his college English instructor and lover fifteen years ago. Cassia tells Jeremy that she has become a full-time peace activist with the International Cooperation Committee (ICC). The ICC runs a home for runaway girls. They are both the children of holocaust survivors The ICC is funded by Helping Hands, a charity with terrorist ties under investigation by the Justice Department.

Jeremy confronts Cassia’s extreme views by placing cartoons parodying the ICC on Cassia’s blog. They spar—his version of history v. hers. Finally realizing Cassia is intractable, Jeremy points a water gun at the lens of a camcorder and squirts. He posts the clip with the caption: “What we need is to shorten history.” Cassia interprets it as a murder threat and obtains a temporary restraining order against Jeremy. Her daily presence in the Coffee Exchange means that Jeremy is unable to come to work. Dita Marx devises a way for Jeremy to enter the Center an hour before the Exchange opens and moves his studio to the top floor. When Cassia is found murdered in a restroom in the basement of the exchange, Jeremy is arrested.

Suspicious of the ICC, Dita decides to go undercover as a volunteer. She takes her former dance partner CJ and his significant other Neil along with her. Hilarity ensues.

The murder of Cassia and the disinformation she hears at the ICC makes Dita and her husband Dan embark on a spiritual journey. Dan has decided to convert to Judaism. They study at the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Meanwhile Dita’s students are performing for Summer Solstice in Central Park. Cravens and cohorts have planned massive demonstrations throughout New York City on that day but Helping Hands has betrayed Cravens and plans a terrorist attack.

Two of Dita’s students wander into a cave in the park to share lunch where they are confronted by a suicide bomber. They make a miraculous escape. Dita comes to look for them and she, CJ, and Neil are taken hostage and made to put on vests which the terrorist will detonate by cell phone unless some way can be found to jam the signal.

PROLOGUE

North Woods Central Park

A majestic old elm stood barren of foliage. The height and weight of its limbs posed a danger to the public it had once sheltered. The winter had been harsh, and perhaps the beloved old tree had succumbed to the extreme cold. A team of tree surgeons sent by the parks department arrived in a trailer laden with heavy-duty machinery to take it down.

The team sent one man high in the tree to rope, saw and drop the limb. He secured himself by rope to the upper trunk. His buddies on the ground stood back as he began to saw. When the limb hit the ground with a dull thud, they would then run in, grab it, and take it to be sawed into smaller pieces they fed into a woodchipper. The old elm would become mulch for its newer descendants. They worked swiftly in this manner until only one branch remained.

The man in the tree was thinking about how they would have a beer when the job was done. He wrapped his ropes around the remaining branch. Only twenty feet of the old elm remained standing, leaving a clearer view of this wooded section of the park. The man aloft caught a glimpse of what he thought was a human limb, shallowly covered in a pile of leaves. He called to his colleagues, but the noise of the chipper was too much so he disconnected himself from the tree trunk and clambered down. He hit the ground with a running stride, thinking someone was sick or injured. He motioned for his fellow workers to shut down the machine and follow him.

Up close, they realized it was the body of a young woman beyond help, and summoned the police. Her body and face were battered. The medical examiner arrived quickly to process the scene. The broad cheekbones and widely set eyes suggested to him that she was of Eastern European descent. The brassy peroxide tint of her hair suggested an old Soviet beauty salon. The poor woman lacked any form of identification.

The police sought help from the public to identify the woman. A police artist’s rendering of the dead woman’s face was quickly circulated in newspapers, on television news, and in flyers posted on lampposts, bulletin boards, and wherever the public gathered.

CHAPTER 1

Here comes that lady professor,” Albert Bliss whispered to Nick, his boss at The Coffee Exchange. That’s how he referred to Cassia Warshaw, who had been an instructor in English at a major university but had, according to her, resigned under coercion by jealous academics. She’d written an article for a radical left wing publication about her experiences with the university entitled BLACKLISTED. She’d left copies of her article in a rack the Coffee Exchange provided for its customers, to circulate flyers and free newspapers.

In the article, she alluded to a lawsuit she had filed in Federal Court against the university for gender discrimination. It described at length the toxic work environment she had been subjected to. Everyone who read it felt it was over the top and wondered what she was trying to achieve. The litany of complaints included sexual harassment, exclusion from discussions with the other faculty members, and a glass ceiling. She claimed that in her initial year, the male faculty and staff had made an effort to intimidate her. She described an encounter alone in an elevator with a male colleague. “You should be afraid to ride with me,” she said he told her.” She described how she once found a swastika affixed to her office door. “They were conspiring to make sure I’d fail,” she wrote.

Now she frequently spent afternoons in the Coffee Exchange where she kept pretty much to herself, despite the gregariousness of the place. As usual, her first stop upon entering the Exchange was to secure a table for herself, her second was to check that her missive still occupied space on the rack. Today she found it covered by the fliers of the dead woman. She stared at the police rendering, picked up a copy, and brought it to the table.

The second Nick turned on The Coffee Exchange neon sign with its 1950’s cup and saucer in pink, gray, and black, customers began to straggle in. Saturday mornings were always hectic. Sixteen-year old Albert had a towel slung over his shoulder and was washing and drying mugs as fast as he could to keep ahead of the late Saturday morning crowd now filling up the Coffee Exchange. By late Saturday morning, the Coffee Exchange was very busy. Albert also needed to wipe down some tables. Tables had to be shared. The lady professor, he’d observed, never allowed anyone to sit with her. Instead, she sprawled her stuff across the table, staring intensely at the screen of her MacBook Pro. Today she seemed riled by something as she approached the counter.

“I’ll take the Niçoise but hold the anchovies, egg and beets,” she told Albert. “And I’ll have a cappuccino.”

Albert went to the back where Nick was preparing food and returned with the reduction Niçoise. “That be eight dollars,” he told her.

“But I asked you to hold the egg, the anchovies and the beets, so it’s got to be less. How about I pay you six dollars.”

“I don’t have authority for that. I’ll talk to the boss.”

He went to the back and told Nick that the lady professor wanted to discount her salad because she didn’t want certain things. Nick wiped his hands on a towel and came out to the register. A long line had already formed out of the front door.

“No can do!” Nick told Cassia. “I can’t run my business that way. Would you like to have some bread with your salad?”

“I’m gluten intolerant. I’m allergic to eggs, and I detest anchovies.”

A customer in line behind her spoke up. “C’mon lady, I have a short lunch hour today. I can’t wait for you to bargain him down.”

She turned, gave him a hostile stare, and haughtily pulled out a ten-dollar bill. Albert made change and she dropped two quarters in the tip jar. “I’ll bring the cappuccino to the table when it’s ready,” Albert told her. She returned to her table with her salad.

Albert fiddled with the espresso maker and the dark, rich liquid was expelled into the cup, to which he added milk he steamed in a stainless pitcher. Nick had taught him how to make coffee, and Albert was on the way to becoming a barista. He loved drawing symbols in the foam. Today he swirled the milk and the espresso into a heart and trotted over with it to Cassia Warshaw. That should make her feel good. She barely acknowledged him as he set the cup before her. She just kept staring at the flier of the dead woman.

Nick stayed out front to help Albert take orders. Albert needed to leave at 1 PM for American Ballet School. Lean, brown and lanky, Albert seemed to grow daily. He helped out at the Coffee Exchange on Saturdays when he didn’t have morning ballet classes. Men’s class was scheduled for 2 PM today. It was Albert’s favorite class of the week. Women from the parent company took it for the challenge. He got to do lots of fouettées.

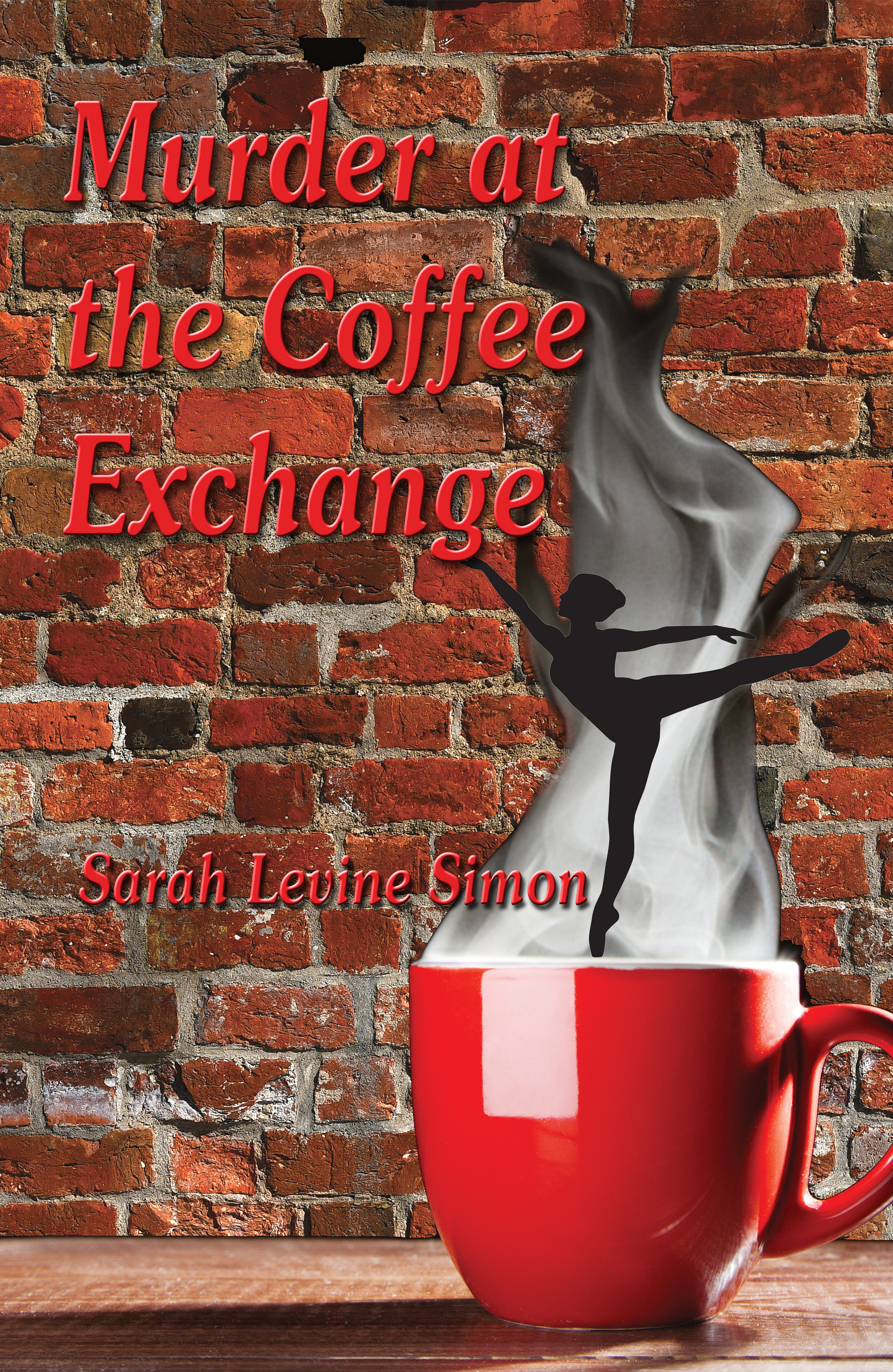

The Coffee Exchange occupied the ground floor of one of two brownstones housing The Harlem Center for the Arts. Harlem—more than anywhere else in Manhattan—now represented a melting pot with its street buzz of foreign languages, as well as the dialects of black and white Americans. Within the radius of several blocks, a person could eat Ethiopian, Greek, French, Soul food, and many other cuisines both in restaurants and from the prolific street vendors. The Coffee Exchange served an eclectic menu at the whim of its owner, Nick Alexander.

The usual crowd from the Center entered during the lunch hour. The Center’s artistic director, Dita Marx, pushed her baby Violet Marjory in a pram. Sylph-like, Dita had wavy brown hair, almond shaped hazel eyes, and a generous sprinkling of freckles across the bridge of her nose. The baby favored her husband Dan, with dark hair and dark eyes. She frequently came to work with Dita. The two doting African-American godmothers, Violet Peters and Marge Bliss, walked beside the pram. They made funny faces, making the baby laugh. The baby carried their names. She now sat up and had begun to crawl. Dita, Violet and Marge were going to have lunch with Jeremy Windt, a new teacher hired to teach cartooning to the Center youth. Jeremy entered a few seconds later, and took a seat next to Dita.

Dita’s group occupied a large round table across from Cassia Warshaw, who barely looked up from her computer screen except to sift through her salad with a fork and isolate some more of the ingredients.

When they were seated, Marge Bliss announced, “Okay, y’all. This is on me. What’ll it be?” They had a tradition of taking turns to buy lunch for the group. They turned and stared at the blackboard announcing the specials and gave her their orders. She went up to the counter to order from Albert. He was her grandson.

The baby began to fuss. Dita picked her up and covered herself in a poncho to nurse her, causing Jeremy to try and seem like it was the normal thing to do. He had never been around babies, so he looked away and recognized Cassia Warshaw with a jolt of embarrassing memories.

What if she recognized him, too? Not wanting to seem rude, he then excused himself to say hello. “She was my English professor fifteen years ago,” he told Dita. Would Cassia remember him as a scrawny fawning kid? Here he was looking a bit middle-aged with a belly on the way to paunch, and thinning hair he pulled into a ponytail. He had watchful hazel eyes and eyelids that wrinkled humorously in the corners. He stood just about six feet but seemed shorter as he stooped a bit from the hours spent at the drafting table each day.

He’d developed a cartoon persona. He favored brightly colored neckties and wore canvass Keds he decorated with his own cartoons. He also had an extensive wardrobe of tee shirts he decorated with more of his cartoons. Today’s portrayed the grim reaper as a stooped old man bent over a cane. “My time has come,” read the caption. Jeremy was mocking death.

“Jeremy, are you living around here?” Cassia asked as she looked up in surprise. He remembered the flat affect and monotonous speech pattern except when she was roused to anger. Anger seemed to enliven Cassia.

“I have a new job teaching cartooning in the arts center.”

“So you’re still cartooning. Would you like a seat?”

“I’m eating over there with my new bosses.” Cassia glanced briefly across at Dita’s table. Jeremy remained standing as he asked if she was still teaching at GWD, where he had honed his skills.

“The school was allowing my email to be spammed by pornography. They engaged in a campaign to get me to resign. I can’t begin to tell you what I lived through.”

“I’m sorry you went through that,” Jeremy said awkwardly. He wanted to seem sympathetic despite knowing she exaggerated—that was Cassia.

“But that’s all in the past. I just went on a freedom flotilla to Gaza to help women and children. My organization sponsors a home here in New York for runaway girls. I work as a counselor and advisor to them. They come from all over the country. It is wonderful to be a part of this kind of activism—to bring hope to the downtrodden. Show them a future.”

“But there are many organizations that help runaways that aren’t sponsored by an anti-Israel group,” Jeremy responded. You could probably go to Israel and do this work. I thought you were Jewish, Cassia.”

“I am. My mother’s parents died at Auschwitz. But Israel has become an apartheid state. I can’t bear what she has become.”

“Cassia, that’s very harsh statement. You seem to be off on two different tangents. Israeli women have the same rights as men. Do you see that in the rest of the Middle East? It’s hypocritical.”–she didn’t answer his question–“If you want to help women, then you have to champion full rights for all women.” He remembered how she used to block off anyone who disagreed with her. He’d seen it over and over again while watching her teach. He’d been too young to consciously process her motives and he’d felt an attraction toward her.

He remembered her assigning him Franz Fanon to read in her Post-Colonial Literature class. He’d timidly questioned her about the writer’s anti-Semitic views. She had taken him under her wing and explained that the writer was only comparing the plight of the blacks to the Jews. Internalized oppression, she’d called it. And he had drawn a cartoon of a man internally oppressed with little pacmen running through his pinball machine-like guts. One thing led to another. She was physically attracted to him as well, and one afternoon she invited him to sleep with her. She was twelve years his senior and Jeremy had been a virgin at the time. Cassia had come through a bitter divorce and had regaled Jeremy with the details. He remembered wondering how she could have married someone she found so flawed.

Jeremy had been approached by some of the other Jewish students in his class to challenge her on some of her views—they smacked of self-hatred. Sometimes a thread of reality seemed to run through Cassia’s distortions and sometimes she outrageously distorted it. He remembered she’d showed them a film of the Algerian revolution, never once mentioning that during it Jews were again displaced by history and alluding to the Jews as colonizers. Forget the French. In Cassia’s version, they barely existed.

His parents were friends with Algerian Jewish refugees who left thriving businesses behind and barely got out with their lives. In his university days, Jeremy had been too enamored of Cassia to join his fellow students in their criticisms. Now hearing about her talk about joining a flotilla endangering Israeli soldiers, he really regretted that he had downplayed her politics for the sake of sex.

Jeremy glanced over at Dita and company, and saw that Albert had brought over the dishes they had ordered. Jeremy watched as Albert’s grandma Marge demanded a kiss and a hug from the boy. She had told Jeremy she was so proud of Albert. He excelled as a ballet dancer.

Jeremy had learned from Marge that Albert’s mother was about to be released from jail after serving a ten-year sentence for a minor drug offense. There would be a lot of celebrating at the center. While incarcerated, she had managed to finish high school and obtained a college degree through a correspondence course. Jeremy loved this new group of people who had welcomed him so warmly. He wouldn’t get involved with Cassia again, he promised himself.

“A discussion for another day. I’ll see you around,” Jeremy said to Cassia, and took his seat next to Dita where the broccoli quiche he’d ordered was still steaming.

“I’ve never seen her talk to anyone in here except to complain about something she eats,” whispered Marge to Violet. “She’s become a regular in the past two weeks, however. I don’t think she leaves the place all day. Maybe she lost her job. You know when somebody gives off vibes. Those aren’t good vibes.”

Jeremy nodded. “The ivory tower.” His cartooning mind pictured a cap and gowned academic skewered on a tusk of ivory, and he sketched it on the butcher paper table covering.

Dita laughed and showed the cartoon to Violet and Marge. She brought the baby out from under the poncho, then the conversation turned to what they were eating. This was a group of people who could talk food non-stop.

Dita ate the quiche as well, and Violet had red lentil soup. Marge had the small Mediterranean platter composed like a still life with stuffed grape leaves, dollops of hummus and baba ganoush with an Israeli salad of cucumbers and tomatoes, chopped with scallions. The dish was scattered with olives, and little quarters of pita bread framed the plate.

Nick was doing well. The Coffee Exchange drew a crowd the day it opened. It didn’t hurt that a murder had been committed next door.

![]()

Jeremy’s first full day of teaching commenced the Monday after the Saturday lunch. There were already waiting lists for his class. The art studio occupied the ground floor behind Dita’s office. Dita’s husband Dan had come to the Center at ten AM to take the baby home for a nap, freeing Dita to listen in on Jeremy’s lesson. She heard snatches of Jeremy explaining to a group of children seated at a round table.

“If you arrange simple shapes ahead of time, it will help you to build a framework.” He showed them a drawing of the Mona Lisa and then reduced it to a framework. He asked each child individually what he wanted to draw. Their ideas ran the gambit from insects and elephants to graffiti. One child drew outer space characters. Their interests ranged widely.

“Why draw Martians?” She heard him ask a ten-year-old boy.

“They’re more normal than earthlings,” the boy said.

“In what way?” Jeremy asked.

Another child chimed in. “They don’t act like they know everything.”

Dita heard pencils grazing the pulp paper as he walked around making suggestions. She smiled. Jeremy was a good new hire. She left her office and went over to the Coffee Exchange to meet with Mindy Rothman, her new dollar-a-year executive director.

Mindy had chosen a small table in the Exchange that barely seated two to give them some privacy. They had become close friends. Dita wanted to choreograph a new dance for the summer solstice in June. It was May, and she was under pressure to create the dance. Mindy was solidly behind her, and had raised enough money to pull the project off. Dita had plans to erect a temporary dance floor under a tent in Central Park. The city parks administration was behind the project as well. Dita wanted to focus the piece on Albert and a young Brazilian dance student named Flora Vega. Dita had trained both at the Center and sent them on to her own alma mater, American Ballet School. She would use her center’s students for a corps and the coveted small roles in the performance.

Behind Dita and Mindy, Cassia Warshaw had commandeered her usual table and was typing on her laptop. Jeremy was now between classes and entered the Exchange to buy himself a coffee to go. Cassia beckoned him over. She had been thinking about the possibility of resuming their relationship. “Are you married now?” she asked him.

“No, just ended a long relationship. You?”

“Never remarried. I like to keep things simple to focus on my real objectives.”

“Is that what you are writing about?” he asked.

“I have a blog. Would you like to sit?”

“I just came to get a coffee to go. I have another class in ten minutes. What are you blogging about?”

“If you must know, Jeremy, I keep tabs on the brutal acts of terror Israel commits against the Palestinians.”

“That’s so preposterous, Cassia. How did you manage to get caught up in that dialogue?” Something just snapped inside Jeremy, making it easy to confront her this time.

Cassia reeled from his scathing remark. “You’ll find everything on my blog at FreedomFlotilla/Wordpress.com. I took a long journey to finally understand what the narratives that I studied and taught you as a student were really about. I’d like to share it with you.”

“You assigned us hard core anti-Semites, as I remember.”

“You’re referring to Fanon? It’s nonsense to call Fanon an anti-Semite. He was struggling for a discourse on colonialism that didn’t exist at the time.”

Mindy leaned in and whispered to Dita. “This can’t be going in a good direction.”

Dita rolled her eyes. She was a Jew married to an Italian. Dan didn’t go to mass or practice religion per se, but she and her husband both held strong sentiments about the survival of Israel. Dita privately cheered Jeremy on.

She determined right there and then that she would learn more about the Middle East. She had traveled to Israel with her parents when she was in the second grade. She remembered the country’s vibrancy, but much of their tour had gone over her head. She knew too little and was hesitant to confront anyone on the subject. That Israel could be compared to the apartheid South Africa puzzled Dita. She knew South Africa from reading Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee. You had only to look at photos of an Israeli market place and see the diversity present to know that this was not apartheid.

“But now it’s important for me to act,” Cassia continued.

“So you don’t teach at all anymore?”

“I teach by my actions now.”

“Well I better go teach by my actions. I’ll see you around, Cassia.”

“Oh you will,” she gave him a coy little smile. I know I should not trust him. I’m in an unfamiliar place, she told herself. But it would be fun to tangle with him once again.

Jeremy ordered his coffee black from Nick, paid, and left the Exchange sipping through a plastic lid. Cassia Warshaw’s new-found attitude toward her own people made him very uneasy. He determined that he would confront her on her blog. His family had a Holocaust history, too. His father had survived Auschwitz, and came alone to America as a teenager. His father’s entire family had perished. He wondered how Cassia could have gotten so twisted.

Jeremy finished teaching his class and once more returned to the Coffee Exchange—this time with his laptop.

Cassia was still sitting there, fixated by what she saw on her computer screen.

He Googled her name and was easily led to her blog. It was the most anti-Semitic bilge he had ever read. It astounded him that these sentiments could be written by a Jew. She was reposting a false story about how Israeli soldiers shot bullets at the flotilla, and how the United States government wouldn’t help the people on it.

Jeremy responded in her comments box that the bullets were made of rubber. He remembered reading about the incident and the unfair treatment of the Israelis by the mainstream media. The flotilla members had clearly come for a confrontation, and not for peaceful purposes. They were swinging chains at Israeli soldiers, who offered to bring the humanitarian aid the flotilla crew claimed to be bringing to the people of Gaza by land. The Humanitarian aid, according to the Washington Post, consisted of two cardboard boxes.

Jeremy shared the headline with Cassia. She looked over at him, annoyed. He shot off another comment on her blog: “What if your beloved Gazans found out that you are a Jew? It’s so preposterous that a Jew and child of Holocaust survivors would turn against her own people.”

She countered, typing furiously. “I haven’t turned against my own people, only the Zionist policies of the Israeli government.”

“Cassia,” Jeremy said, “What I support is a real peace between a Jewish state of Israel and an Arab state of Palestine. That’s something to hope for.”

“What I support is equal rights for everyone,” said Cassia. She evaded the implication of what a real peace could mean. There wasn’t even a two state solution in her dialogue like so many idealistic, well-intentioned people proposed for the region. Hers was a politics of rage, he thought. She was clearly aligned with groups that didn’t think Israel should exist—that there shouldn’t be a Jewish State.

“Under international law, Israel is required to give up all the territory it gained in 1967,” wrote Cassia. More bilge. Should he dignify her with an answer?

“You mean when five Arab countries attacked little Israel. Whose international law do you subscribe to?” asked Jeremy, typing furiously. “Seems to me, Israel is the only country in the Middle East with a fair and functioning legal system.” Jeremy had had enough. He finished his coffee and put his laptop back into its sleeve. He left thinking how her presence in the Coffee Exchange tainted the experience of the novel new place.

The Coffee Exchange owner, Nick, had offered him wall space for a month for some of his cartoons. Jeremy thought he’d go home. He needed to think about what he should hang—maybe go through his art storage drawers.

Once home in his digs, he couldn’t help thinking about how to counter Cassia’s arguments. He opened the laptop again and posted a YouTube video about the expulsion of Jews from Arab lands in 1920 on Cassia’s Facebook page. She took it down immediately. Then he decided to up the ante by creating his own blog to present what he felt were the truths about the conflict.

Jeremy smoked a joint and sipped a glass of red wine. He was going to have food delivered from the Szechuan Star restaurant across the street. He lived in a studio near the George Washington Bridge with barely room for his drafting table, art drawers and double bed, just in case he was lucky enough to get laid once in a while.

He generally felt lonely, but somehow hadn’t succeeded at staying in a permanent relationship. He’d dated a corporate lawyer for several years, but his impulsivity—the earmarks of his type of creativity—irked her. The inequality in their salaries, and her desire that he would just get a job-job finally did the relationship in.

He wasn’t unsuccessful. He’d sell a few cartoons to a syndicated paper here and there. He’d illustrated two children’s books in the past year. But reality was very few cartoonists became rich. He laughed at the macabre thought that he could probably have sex with Cassia Warshaw if he weren’t so intent on confronting her.

A cartoon formed in his mind, and he began to doodle. It was a likeness to Cassia Warshaw giving birth to the head of Hitler. He began to hone the image. He stood the sketchbook up and contemplated his drawing. He thought about Nick’s offer of wall space. Would he dare hang this one in the coffee exchange? Would Cassia recognize it as herself? He was on cartoon autopilot and that could lead to trouble, he well knew. When cartoons became a weapon, they were a distinct liability to the cartoonist. He decided to make the cartoon less of a likeness in the morning. Then if she thought she saw herself in it, she was just paranoid as far as the world was concerned, and he would have succeeded in making a statement.

Maybe make her a blonde. He remembered her telling him that she could make men aggressive by making her hair blonde. She made her hair blonde during the years that he attended college. He was attracted to blondes. For the moment she had returned to mousey brown streaked with grey.

Making feathery strokes with his pencil, he imagined the crowded flotilla barricaded by Israeli soldiers. He sketched out a sea of staunch-looking and determined faces, backgrounded by the shape of a sea-going vessel. They could have been nuns or penguins. It became so crowded he thought about what kind of symbol he could hide among them, what kind of statement he could make. It would be funny to show a sea of activists and two small cardboard boxes labeled “humanitarian aid” being lifted by crane with great fanfare. The caption: It took every last one of us to bring you aid.

Then he had another idea. He sketched out Lady Justice wearing a burka and her sword, with a machete leaned on one arm, her other hand holding the fulcrum balancing the two trays. A dismembered head sat on each tray—his caption for one; “Want Statehood,” the other; “Want to kill Jews.” He photoshopped the sketch and posted it in the reply column of Cassia’s blog. The hour was late and it remained on her blog until ten AM the following day.