BY: PAUL SINOR

BY: PAUL SINOR

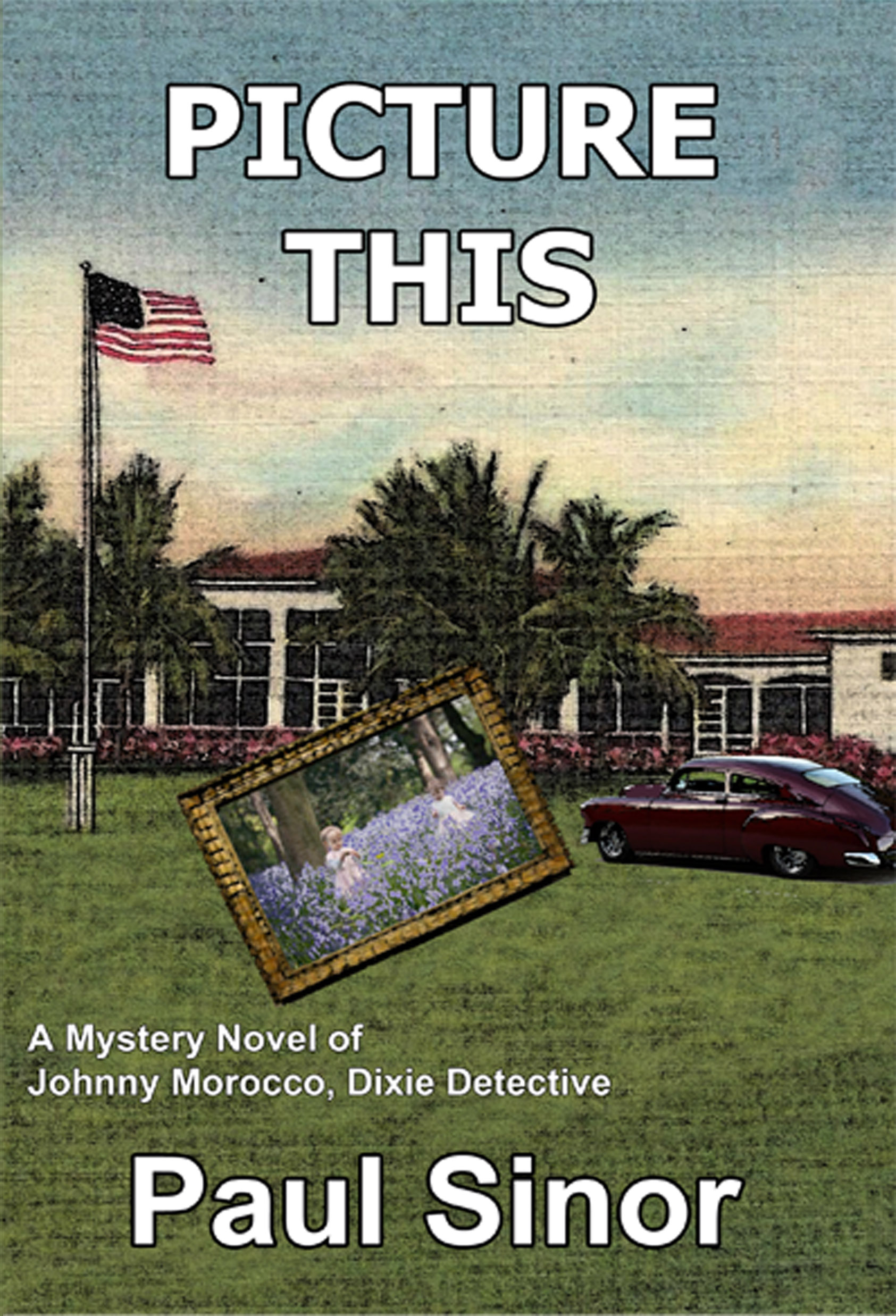

A valuable painting goes missing from the governor’s mansion during a party Johnny is attending. He is asked to find it. The search leads from Atlanta to West Palm Beach, Florida. There he finds there is a time for everything including theft, con games, lying, deceit, fraud and attempting to regain what he left behind.

TAYLOR JONES SAYS:

REGAN MURPHY SAYS:

CHAPTER 1

Johnny Morocco did not own a suit or a tie and had not worn one since he was released from the Army in 1946. At that time, he swore he’d never wear another one of either. So far he’d manage to keep that promise he made to himself. When he changed his name from Johnny McDonald and began working as a private investigator in Atlanta he’d dressed in casual pants and shirt. He owned a couple of jackets but they were either for cold weather or to hide the Colt 1911 model.45 automatic he sometimes wore in his shoulder holster. When he went to his new office at Big Town, a pool room in downtown Atlanta, none of the regulars cared how or even if, in all likelihood, he dressed.

All of that changed in October when he got a job protecting a prize stud bull at the Southeastern Fair. The bull belonged to the father of the woman who called and told him he needed a suit and tie. Not only had he gotten a job, but he had met the daughter and they had been together since.

He parked his car across the street from Big Town and walked half a block to the diner where he normally had breakfast. Miss Ruth, the owner of the boarding house where he lived on Ponce De Leon Avenue, cooked a massive breakfast for all the borders. Most of the time Johnny preferred a quiet booth in the corner of the diner where he could read the morning paper and linger over a second cup of coffee. Mildred, his usual waitress, slid a heavy white mug of coffee in front of him as soon as he settled into the booth.

“Mornin’ Darlin.’ You eatin’ or drinking or both today?” She stood by, order pad and pencil in hand indicating she was ready to write down his order if necessary, but there were few times she actually put pencil to paper. Once the customer gave her his or her order, it was called out to a cook who by some magic, managed to keep all of them in his head. Customers hardly ever had to send an order back because it was wrong.

“Coffee, eggs over, grits, crisp bacon and a biscuit.” Johnny looked up at Mildred as he folded the paper and propped it up between the napkin holder and a bottle of ketchup, so he could read it while he drank his coffee.

“I don’t know why I even ask. It’s always the same unless your friend the cop, comes in and mooches off you,” she said as she walked away.

Johnny and Atlanta police Detective Sergeant Jack Brewer had a friendly adversarial relationship. When Johnny had been hired to watch over the stud bull, a man had come into the stock exhibition hall one night and tried to castrate the bull. He attacked Johnny and wound up on the floor bleeding from two holes Johnny had punched in his chest with his .45. His father and three brothers took it personal and came to Atlanta with revenge and blood on their minds. It ended with Johnny and Brewer in a gun battle with them in a restaurant where Johnny was shot, and Brewer had to shoot and kill a man for the first time.

It was not unusual for Brewer to come to Big Town at lunch time and talk to Johnny and harass some of the locals who hung out there. More often, though, he stopped by the diner in the mornings and picked a piece of bacon off Johnny’s plate and drank several cups of coffee and let Johnny pay the bill.

This morning Johnny ate alone and in peace. When he finished, he paid the bill, left Mildred a quarter tip and headed across the street to begin his day.

Big Town was on Edgewood Avenue and near the center of the city at Five Points. If anyone wanted directions, it was provided with Five Points as the starting place. Johnny stopped as one of the city’s electric trolley’s came by. When the city got rid of trolley’s on rails, it went to electricity. Each bus had two long poles attached to the top of the bus that rode along overhead electric wires strung throughout the city and into the suburbs. It was not unusual for the leads to slip off when the busses went through an intersection where the lines crossed. Johnny watched as this bus successfully navigated the intersection and went up Peachtree Street. The bus cleared the intersection and Johnny prepared to step into the street. Early morning traffic was already beginning to build. Most people who worked in Atlanta rode the bus to work, so the cars were mostly tourists, salesmen, or those who did not want to put up with riding a bus.

An old Plymouth pick-up truck passed him and left a trail of black exhaust smoke in its wake. The windshield was rolled out about four inches so the driver and any passengers could get fresh air when they were forced to endure a ride in the ancient machine.

Johnny was still coughing when he heard the sound of someone yelling on the corner. He was wearing a light jacket and instinctively pressed his left arm to his body to make sure he had his weapon on him. He felt the bulge of the pistol in the holster as he turned toward the sound.

Once he located it, he realized it was not someone yelling but rather someone preaching. He shook his head and continued his journey to Big Town. He knew the man on the street was one of the regulars at Big Town. He was an accomplished pool player, always up for a game of poker and was known, by everyone only as Preacher. Like most of the men who frequented the downtown pool room, they all had lives that they had either already left or were making a gallant effort to leave behind them. Very few went by a birth name, so it was not unusual to hear the owner, known as Hockey Doc, call out food orders from behind the counter for Crip, Peg, Sheriff, Babe, or Preacher.

When Johnny climbed the steps to the second floor, the first thing he saw, as usual, was the large Army surplus coffee maker sitting at the end of the counter. Beside it was a cigar box with the top torn off. The men who called Big Town home on a daily basis were not the highest level of social acceptance. Most had served during World War Two and had come home to less-than satisfying jobs if they could find jobs at all. Many had served time in a variety of city, county, and state lock-ups for offenses that they did not mention, and the majority were chronically unemployed and in debt up to their eyeballs.

They shot pool for a quarter or fifty cents a game, bet on baseball games that played on the radios placed on shelves above the tall chrome and leather-seated stools that lined the wall, hustled anything and anybody they could. They did that day in and day out but they dropped five cents into the cigar box for every cup of coffee they drew from the pot. There were no free refills at Big Town. You poured, you paid.

Johnny dropped a nickel in the box, grabbed a mug, checked to see if it was clean and when he was satisfied that it was, he pulled down on the black handle and placed the cup beneath the stream of coffee. “Mornin’ Doc. How’s it going?”

Hockey Doc was busy filling a steamer with uncooked hot dogs. “Same as always. If you guys don’t start buying more food and beer, I may have to close this joint. Them pool tables don’t hardly pay the light bill.” He placed the last hot dog on the rack and turned to the steamer beside him and began to load it with buns.

Johnny let go of the handle and pulled his mug of coffee toward him and took a cautious sip. “Coffee’s not bad this morning. You must have let Billyhart make it.”

“I heard that, Mister Johnny. You don’t need to be talkin’ like that or Mister Hockey Doc will run both of us off.” Billyhart was the combination rack boy and janitor. His name was really Billy Hart, but he had a slight lisp and when he answered the phone it always came out, “Dis ith Bic Town. Billyhart speaking.”

After working out of Big Town for several months, Johnny had made a deal with Hockey Doc to rent a small storage room that was not being used. He turned it into an office and still used the pay phone in the pool room to conduct business. He paid Billyhart to answer the phone and clean his office for him. Johnny took his coffee and was headed to his office when he heard the phone ringing in the phone booth. It was too early for any of the players to be there, so he assumed it may be for him.

“I got it,” he said as he pulled the door open and stepped inside.

“This is Johnny, can I help you?” Hockey Doc had been adamant about having the phone answered by saying it was Big Town. If it was for Johnny, that could be explained away if necessary. Billyhart always answered like he was supposed to, but Johnny used his name on the rare occasions when he answered.

“Johnny, it’s Gina. You have a minute for me?”

©2020 by Paul Sinor