BY: JUDITHE LITTLE

BY: JUDITHE LITTLE

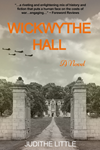

May 1940. Hitler invades France, a move that threatens all of Europe, and three lives intersect at Wickwythe Hall, an opulent estate in the English countryside—a beautiful French refugee, a take-charge American heiress, and a charming champagne vendeur with ties to Roosevelt and Churchill, who isn’t what he seems. There, secrets and unexpected liaisons unfold, until a shocking tragedy in a far off Algerian port binds them forever…

Wickwythe Hall is inspired by actual people, places and events, including Operation Catapult, a sea action in which Churchill launched a bloody attack on the French fleet to keep the powerful ships out of Hitler’s reach. Over 1,000 French sailors, who just days before fought side-by-side with the British, perished. Humanizing this forgotten piece of history, Wickwythe Hall takes the reader behind the blackout curtains of upper-class England, through the bustling private quarters of Churchill’s Downing Street, and along the tense back alleys of occupied Vichy, illustrating what it took to survive in the dark, early days of World War II.

TAYLOR JONES SAYS: In Wickwythe Hall by Judithe Little, Annelle LeMaire is living in a convent in France and about to become a nun when Germany invades France in 1940. Afraid for her brothers who were shipped off to serve in the French Foreign Legion, she runs from the convent as the German soldiers arrive in her small town. Fleeing before the German Army, she makes her way to England, where runs into Mabry Springs, mistress of Wickwythe Hall. Mabry takes Annelle under her wing and gives her a place to stay and work while they search for a way to contact her brothers somewhere on the continent. As Mabry and her husband Tony are part of the English aristocracy, many important people come to Wickwythe Hall, including the prime minister, to debate about the war and plan strategies. But everyone seems to be hiding something.

The author has a fresh and enchanting voice and her character development is superb. It will give you a glimpse into life during wartime in a way that makes history come alive. A truly compelling read.

REGAN MURPHY SAYS: Wickwythe Hall by Judithe Little is the story of a young woman who escapes France just ahead of the German Army. Just a few days before she is to take her vows to become a nun, Annelle LeMaire flees her convent as German soldiers flood into her small village. She tries to warn the nuns, but they refuse to leave the convent, so Annelle goes alone, determined to find her two brothers who are serving in the French military. She doesn’t know where they are, or how to find them. When she reaches the coast, she manages to get on a boat and crosses the Channel to England. Once there she meets a wealthy American heiress, Mabry Springs, marred to an English nobleman. Mabry takes Annelle home with her to her estate Wickwythe Hall, where important politicians often meet, hoping that somehow she can help Annelle find her brothers in France. But as the war progresses, not only are Annelle’s brothers at risk, but everyone she has come to care about in her new country.

Beautifully written and told in an engaging voice, Wickwythe Hall blends fiction and history to give us an enlightening and thought-provoking look at a time in history when so many sacrificed so much. A marvelous accomplishment for this talented author.

CHAPTER 1

Annelle LeMaire

France: May 1940:

Outside the convent kitchen, a truck rumbled past.

“Sister,” Annelle said. “That’s the fifth to go by.”

“Yes,” Sister Marie Michel said, not bothering to look up. “Now try to be still.”

Arms out at her sides, Annelle balanced on a rickety wooden stool, worn and curved at the center from so many feet before hers. Sister Marie Michel’s skirt rustled as she crouched low on the rough stone floor stitching the hem of the gown Annelle was to wear down the aisle. It was a simple white sheath with sleeves to her wrists and a high collar. It made her skin itch and her face flush. She wanted to loosen the seams, stretch the tight weave of the cloth. Instead, she swallowed hard. “These trucks,” she said. “They sound like army trucks.”

“The vows bring such marvelous enrichment,” the nun said, as if she hadn’t heard. “The ultimate act of giving oneself, to give your whole being in sacrifice to another…”

Annelle shifted her weight. The stool wobbled. She felt a sharp, quick pain at her ankle.

“Mother Mary, I stuck you,” Sister Marie Michel said. “Are you all right?” She looked up at Annelle with kind blue eyes that had soothed skinned knees and night terrors. Twenty years had passed since the accident when Annelle, two years old, and her brothers, seven and eight, were orphaned and brought to the convent to live. Sister Marie Michel, like all of the sisters, had cherished and loved them as if they were the nuns’ own flesh, maybe more so because the nuns didn’t have that option. And now the day was coming, the day the sisters had kept tucked in their hearts since Annelle had arrived, the day they’d give her away.

“It’s fine,” Annelle said. The stinging at her ankle felt strangely good, something to think about besides army trucks and wedding dresses.

Sister Marie Michel continued stitching. “…a love that is gentle and kind…the most holy union…a ceremony sanctified and sacred…”

Annelle closed her eyes. In one week, she would be the bride of Christ. One last week, before she gave herself over to vows of enclosure, chastity, poverty, obedience. But her brothers, gone ten months, would not be there to give her away.

“…truly bound to Christ in the most marvelous way…this most holy Groom will never fail or leave you…”

Outside, another truck passed. Annelle opened her eyes. “Something’s happened,” she said. “Something with the war.”

Sister Marie Michel pulled a rosary from the cincture around her waist and handed it to Annelle. She rubbed the beads between her fingers, breathing in Sister Marie Michel’s familiar scent, the earthy mix of her body’s oils and wool habit. The nuns believed it was a sin to look at their own bodies unclothed. On the rare occasions they bathed, they walked into the river fully dressed, black skirts billowing out around them. From the kitchen window, they looked like giant mushrooms, black truffles springing up from the river bed.

“Soon,” Sister Marie Michel said, rethreading the needle, “you’ll be one of us. That’s all that truly matters.”

The rosary dangled to the floor. Annelle pictured herself standing at the foot of the aisle in the white gown and veil. Ahead of her, below the altar, the sisters would gather. Sister Marie Helene with the scissors. Sister Marie Mathilde with the brown robe. Sister Marie David with the crown of thorns and Sister Marie Clare with the plain wooden cross. They’d cut Annelle’s hair, replace the white dress with a brown robe, place the crown of thorns over a new black veil and the cross in her hands. She’d watched the ceremony with her own eyes, how many times? A little girl, curious, hidden behind the smooth wooden back of a pew. She’d be given a new name, Sister Marie Clotilde, that was the name they’d chosen for her.

Outside, another truck went by, moving fast.

She tried to focus on the beads between her fingers. Instead, she thought of war. The headlines last September were bold and black. C’est La Guerre, they’d blared from the newspaper sellers’ kiosks. Annelle had stopped on her way to market to read what she could. Crowds gathered around, people whispering, crying, cursing. Hitler had invaded Poland. France and England declared war. Les Boches, the old French men around town called the Germans, fists shaking in the air. Bad feelings toward Germany ran deep in this part of France. The town was near the French border with Belgium. On this soil, La Grande Guerre was fought, the Battle of Arras, Ypres, Vimy Ridge, the Somme, and Verdun, all of it here or close to here. The fields stretching out around the convent were forever pocked with the remains of trenches, marking the front lines, though they were now almost twenty-five years old. Grass and crops grew over them, but there were patches where nothing would grow, the earth poisoned by the remains of war in its folds. Her brothers, the two boys turned into farm hands, had plowed up bones, skulls, and metal helmets every spring.

Now, France was in another war with Germany. But this time, Annelle reminded herself, it was different. This time, France had the Maginot Line, La Ligne Maginot, a barrier of concrete fortifications built along the border with Germany after La Grande Guerre to keep the Germans out for good. After war was declared last September, French soldiers had been sent to fortify it and to guard the border with Belgium where La Ligne was not built as strong, because, here, the Ardennes forest was impossibly dense, a natural fortification. German tanks, it was certain, could never get through.

That didn’t mean they wouldn’t try. Around town, army camps dotted open fields as far as Annelle could see. British soldiers came too, the two countries united once again to face their German foe.

But from September to May, the soldiers played cards. They drilled. They carried on flirtations with the girls in town. There was nothing else to do. Even though war was declared there were no battles or confrontations. It was called a Drole de Guerre, a joke of a war. La Ligne Maginot was working.

Still, in town, windows were blacked-out. Sand bags appeared overnight, piled up outside buildings. There were new signs posted for cellars turned into shelters. Periodically, practice air raid signals blared. Near the tabac, a line wound round a corner of old women gripping shopping baskets and schoolchildren clutching the hands of mothers with tight smiles.

“What are you doing?” Annelle asked one of the women.

“Getting fitted for a gas mask,” she answered. “Better to be safe than sorry, yes?”

Back at the convent, there were no blacked-out windows, no sandbags, no shelters. The sisters were not interested in gas masks. God would protect them, if that was His will, and they went about their days as if nothing at all was happening.

Annelle glanced down at Sister Marie Michel. The outside world didn’t exist for her. She didn’t know that, just two days ago, the Germans had invaded Belgium, the newspaper sellers’ headlines bold and black once again, taking up nearly half the page. Had the nuns noticed that the French and British troops camped near the convent had packed their tents and left for the Belgian front to stop the Germans? Their trucks, the tents, had all gone, just trampled, empty fields left, clouds of dust stirred up in the breeze.

Outside, another truck barreled past, then another. Plates and pots rattled on their racks.

“Almost done,” Sister Marie Michel said.

Annelle pressed harder on the beads. The soldiers were gone. They were in Belgium, keeping the Germans out of France. There should not be trucks. Sister Marie Michel stitched. Annelle shifted her weight from foot to foot. A bead of sweat trickled down her back. The nuns heard choirs of angels. She heard trucks.

The tower bells rang the hour, as oblivious as the nuns. Sister Marie Michel stood, a satisfied smile on her face. “We’ll finish after Rosary. Hurry now. Change out of that dress or you’ll be late for prayer.”

***

Sister Marie Michel headed for the chapel. Annelle waited until she was out of sight and rushed through the door, lifting the dress above her ankles so she wouldn’t trip. Holding the white postulant’s veil to her head to keep it from flying off, she ran down the hill toward the road until what she saw stopped her short.

British army trucks, overflowing with soldiers, sped down the road, away from Belgium and the German front. Where were they going? Bandages circled the soldiers’ heads and arms. They were bloodied, dirty, shaken, coughing from dirt the trucks kicked up.

“What is happening?” she shouted in English, Sister Marie Michel’s native tongue.

“The Germans are coming,” a soldier yelled back.

A tightness gripped her. She ran closer. “But—but how could that be?”

“They’ve broken through the Ardennes forest,” he called out. “The Maginot Line. They’ve gone around it!”

“Run, sister. Run fast!” another soldier shouted, his eyes wild. “Pray for us all.”

Their voices trailed into the distance, drowned out by the rumbling of the trucks, the grinding of engines. She stood, frozen. The British were fleeing. The French army was too, their trucks mixed in with the British. These soldiers were the defenders. If they were retreating, what did that mean for everyone else?

La Ligne Maginot. She’d seen diagrams of the fortifications in the newspapers, reminding her of pats of butter on a baguette, now turning out to be no better than that.

More trucks passed, and, after them, cars black and speeding, suitcases strapped to their roofs, the faster ones honking at the slower ones in their way. And bicycles. An old man pedaled by, a harvest basket strapped to his back, clothes he’d stuffed inside flying out piece-by-piece, leaving a trail behind him. Two young women dressed in suits cycled past, their backs straight, their expressions purposeful—clerks, probably, in some nearby town. Soon it was all a jumble, dust flying, cars honking, passengers shouting out the windows to get through, bicyclists whizzing past, a man and a girl on a horse. Dogs barked and chased. An old woman in black crepe, her long silver hair hanging to her waist from the remnants of a bun, pushed a cart weighed down with an antique clock and a silver tea set. A mother pulled a wagon filled with iron skillets and copper pans, children at her heels trying to keep up. More cars and horse-drawn wagons went by, wheelbarrows and donkey carts, children crammed in amidst brooms, glass bottles, bed linens, and sacks of flour and potatoes.

It seemed as if all of France had taken to the road.

Annelle looked behind her at the convent. She couldn’t see them, but she knew the sisters were in the chapel saying rosary, their eyes raised to heaven in quiet exuberance, their fingers blindly working their beads.

Run, sister.

***

At the chapel, Annelle pushed open the heavy wooden door. Inside, flames flickered. Incense drifted, sweet and powdery. Low voices chanted. “Ave Maria, gratia plena, Dominus tecum—”

But she’d pushed open the door too hard and, as it swung around, it crashed against the inside wall with a loud bang, metal hardware clanging. The nuns, kneeling and bent over their rosaries, looked up all at once, their prayers halted mid-verse, their faces round and glowing in the candlelight.

“They’re coming!” Annelle said, her voice too loud for this sacred space. “The Germans! They’re coming!”

But the sisters were silent, staring up at her or down at their rosaries. The muffled sounds of car horns, shouts, the great movement of people, wove in through the open door. At last the Mother Abbess spoke, her voice calm, her face placid. “Yes, dear. We know. Come now. Kneel. It is time for prayer.”

“Alors, we have to go! It’s not safe!” Annelle said. “We must leave now!”

A few of the sisters exchanged glances, but otherwise no one moved. Annelle met Sister Marie Michel’s gaze, Annelle’s eyes pleading, the nun’s somewhere else. At last, the Mother Abbess bowed her head. She renewed her chant. “Dominus tecum. Benedicta tu in mulieribus…”

The others joined in, a chorus of whispers.

She felt like a fool. What did she expect? Behind the invisible lines of their world, the sisters didn’t panic. They prayed. She should join them, she knew. Instead, still facing them, she took a few steps backward and stumbled over the chapel’s uneven threshold. Outside, the noise from the road had grown louder, filling her head. She turned on her heels, rushed back to the kitchen, and stopped at the crucifix on the wall, trying to decide what to do.

The crucifix had always been a comfort to her, especially last August when her brothers, Philippe and Francois, were sent away to North Africa, to the training camp of the French Foreign Legion. There had been an incident in town—an argument with the mayor’s son who had called Philippe a Communist because he’d gone off for a year to fight for the International Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. Philippe had punched him. Francois entered the fray. The mayor’s son pressed charges. Prison or the Legion, that was the choice they were given, standard procedure in cases like theirs.

They were put on a train for Marseille with no chance to come home or say goodbye, and now they were soldiers, Legionnaires, in Algerie.

In the kitchen, memories bore down on her. Here by the fire, she and her brothers had slept as children. Here at the old wooden table, they’d eaten every meal. Here at the cutting block, she’d worked while they read the newspapers or argued about when to plow and when to plant, about war, about girls in town. Here at the window, she’d gazed out at the convent grounds, at the river, its metallic presence, its steady flow, and the beet fields beyond where her brothers worked, the scene almost like a painting with its subtle hues that changed with the seasons and the time of day.

Memories of the day they were first brought to the convent came back in flashes: an ambulance in a field, a policeman’s blue cap, her bare legs bouncing on the seat of a car as it rumbled over the bridge to the convent, the nuns coming out the door toward Annelle and her brothers like a swarm of black bees from a hive. Later, Sister Marie Michel had held her close when she told Annelle that her parents, out together for a walk on a sunny day, had stepped on a stray, live German shell from La Grande Guerre, buried beneath a layer of meadow. There were deaths like this every year. It wasn’t uncommon.

No relatives had been willing or able to take them in. They’d slept on cots in the convent kitchen until the day, years later, the Bishop from Amiens decreed the boys, thirteen and fourteen, too old to sleep on convent grounds. Her brothers carried their few belongings out of the kitchen to an old, unused cottage on Monsieur Pannier’s farm across the river.

She looked back out toward the road. The soldiers had thought she was a nun.

“Run, sister,” they’d said.

But she wasn’t a nun yet nor even a true postulant. She’d worn the postulant’s jumper and veil since her confirmation at thirteen to please the nuns and her brothers. She’d been referred to as a postulant since then. It was assumed, never questioned. Her brothers had her future mapped out, as inviolate as the convent walls, as unchangeable as the seasons. They were men. They knew what men could be like, and they would have none of that for Annelle. She would take the cloth. She would be pure and protected, forever safe, forever unspoiled, watched over by the nuns who loved her.

But growing up at the convent, she’d been indulged, expected to take the vows but allowed more freedom than others, including the freedom of time.

“I’m not ready,” she would say whenever the investiture was brought up.

Francois indulged her most of all, pleading her case to Philippe. It was Philippe who had insisted that she take her vows, who had seen their parents killed and the devastation of war in Spain and who wanted his sister safe behind the sanctuary of convent walls.

But Philippe was gone. Francois was gone. Les Boches were coming. The convent grounds were no longer a haven, the distant fields gray and menacing, the river harsh and cold. She wasn’t sure anymore where she belonged. She was twenty-one years old, straddling two worlds, one foot on the ground with Philippe and Francois, the other in the clouds with the nuns. In town on errands for the sisters, she would sneak into the cinema. She rose before dawn for morning prayers but kept tucked in a pocket of her postulant’s apron a round compact of rouge she’d found on the ground outside the Hotel de Ville. She took the Body and Blood of Christ every day, her lips pressed tight against the chalice, the same lips that would secretly finish the cigarettes her brothers tossed away.

And there was more.

Joaquin Cruz, a soldier from the Civil War in Spain who’d escaped to France, worked in a local farmer’s fields, his hair black, his skin brown from the sun, a version of Hollywood’s Ramon Navarro, dark-eyed and mysterious. She brought him baskets of tarts, apple one day, fromage another. She felt easy around him, used to being around men and farmers because of her brothers.

But something that was not at all like her brothers was the desire to reach out and run her hand along his forearm, of wanting his arms wrapped tightly around her. One afternoon, the clouds burst, the rain cool on her skin. Joaquin wiped away a raindrop running down her cheek. That was how it started, a touch, then a kiss, a clap of thunder, and a long, mad run to the cover of the barn where Joaquin was suddenly uncertain, but she was not. She removed her postulant’s veil. It fluttered down behind her.

“I’m not a nun,” she told him, “I’ve made no vows.”

She moved closer to him, he embraced her. She told herself she could stop this at any time, though, in the end, she didn’t. She didn’t want to. Temptation, then mortal sin, carnal union, an offense against chastity. The postulant’s veil lay crumpled and discarded on a hay-strewn floor.

Now, standing in the kitchen, she could still feel his skin on hers, his breath fast, his voice low and urging, whispering words she didn’t understand in Spanish, his lips on her ears, her neck, her shoulders. She had no right to wear a white gown. She had no right to take vows. She was of the world, like her brothers, her blood.

Run, sister.

A heavy pressure expanded and rose inside her, clogging the base of her throat. She glanced over at the chapel. How much more time before Rosary was over?

Her breath came in short gasps because she couldn’t believe what she was thinking. She could go south to Marseille. From there, she could take a boat to Algerie, as her brothers had, then find a way to the Legion training camp in Sidi-bel-Abbes. Maybe she could cook for the Legion as she did for the sisters and had done for her brothers. A crazy idea, but the Germans were coming. The world was on foot, moving in front of her, trying to get out of the path of something terrible, and she couldn’t believe she was having these thoughts. She looked back at the crucifix.

“Tell me,” she whispered, “tell me. What is it I should do?”

If she left, she would have to leave the sisters to their fates, setting off, alone, toward her own. She was still wearing the white dress, and when Rosary ended Sister Marie Michel would come looking for her, ready to finish the hem, perhaps question her about the disruption at the chapel door. If Annelle had to say goodbye, if she had to look at the nun’s plump face, her kind eyes, she wouldn’t be able to leave. Sister Marie Michel had come from Ireland and had taught Annelle and her brothers to speak English, to fish in the river, to ride bicycles. Facing Sister Marie Michel, Annelle would lose any courage she had.

And yet her mind kept working, formulating a plan to take her to North Africa. She remembered that her brothers kept money hidden beneath a loose rock in the hearth of their cottage. She didn’t know if it would still be there. She didn’t know what she would do if it wasn’t. She didn’t know what she would do if it was.

She turned back to the crucifix on the wall. “If the money’s there,” she told it, “it’s a sign. A sign that I should go to North Africa.”

She got on her bicycle and raced toward her brothers’ cottage, not far from the convent. The long narrow road fed into the main thoroughfare clogged now with evacuees, but she rode in the opposite direction, dodging a farm wagon loaded with chairs and mattresses, and farther down the road, pedaling around two lowing cows. She turned in toward her brothers’ cottage. A family of Poles lived there now, hired by the farmer to take her brothers’ place out in the fields. The Poles had looked strange to her in their worn, mismatched clothes, the wife with her head wrapped in a kerchief, her socks pulled to her knees. At the door, Annelle knocked and waited. When there was no answer, she let herself in.

Inside the cottage, everything was wrong, the walls now whitewashed and stenciled in blue. There was a shrine in a corner with a cross, a metal corpus, flowers at its base and a small metal roof over the top. Mushrooms hung from the rafters in long strings to dry. A lace tablecloth covered the old trestle table. She realized, an awful feeling in her stomach, the Poles weren’t out in the fields or in town. They’d run, and in such a hurry their meal was still on their plates. She felt a bowl of soup, and it was warm. What horrors had they seen in Poland when the Germans came? What horrors would happen here?

She walked over to the hearth. A wool coat hung from a nail next to it. A broom rested against the bricks. She took a deep breath. “If the money is there, I will go.”

She tried to pry the rock out with her fingers, hands shaking. When at last the rock came free, a wad of bills, wrapped together in a tight coil, fell out with a soft thump to the floor.

***

In the convent kitchen, she filled a knapsack with what she could. Cheese. Apples. A photograph of her brothers they’d sent from the Legion training camp. On a scrap of paper she left a note for the sisters. Please forgive me. I am leaving to find Francois and Philippe.

There was no time to change. She hiked up her dress and pedaled off, the weight of her knapsack heavy on her back. She could feel the convent, dark and gray behind her, trying to pull her back out of this chaos, clutching like old bony hands. The road was a ribbon curving into the unknown.

She joined the crowd of refugees. A man somehow managed to push a piano on a cart. Two old women walked together, looking like they were wearing every item of clothing they owned all at once, one of them pressing several photographs in frames to her chest. A young woman in a faded blue dress gripped the hand of a saucer-eyed little girl holding a home-made doll.

In town, she went directly to the train station but couldn’t get near the door. Suitcases, the collage of people from the road, old, young, rich, poor, filled every space, distraught, trying to decide what to do.

“They aren’t selling any more tickets,” someone shouted.

“The trains are full,” said another.

She got back on her bicycle, telling herself she’d ride to the next town, and the next one after that, until she found a train to Marseille. The crowd pushed her along, past the village that was her home, toward places she didn’t know, and she had to ride slowly. There wasn’t room to move fast.

Voices came from all directions.

“The Germans are a day’s march behind.”

“No, an hour’s.”

“Did you hear? There was a counterattack in Arras. The Germans are retreating!”

“Retreating? You idiot. We are the ones retreating!”

She’d been on the road for over an hour when an old man waved his arms at her to stop, his face unshaven, his eyes yellowed. Where his left arm should have been his shirt hung empty. She took a foot off the pedal and put it to the ground.

“Goddamn Germans,” he said, and from the way he said it, she knew he’d lost his arm in the last war. “On your wedding day, of all days.”

She looked down. The white dress.

Tears filled the man’s eyes. “What’s become of your groom?” he asked.

“Heaven,” she said, and it wasn’t a lie. “He’s in heaven.”

The old man shook his head then moved on. She did as well, weaving through the crowds down long stretches of road surrounded by nothing but fields and scattered farmhouses. No cows or livestock roamed the pastures, and she realized they’d been gathered up. They must be somewhere on the road, refugees like their owners.

The sky was the blue of the Virgin Mary’s robe. The temperature was not too warm, and there was a light breeze. What did it mean that the weather was so beautiful on such a terrible day? She thought of Joaquin and sins against chastity. She thought of Adam and Eve and Sodom and Gomorrah cast out of their homes.

After several hours of traveling, the convent was miles behind. By now, Sister Marie Michel would have read her note. The nuns would know, and she was glad. They would pray for her. At last, she came to the next village, a place she’d never been to before, though it was similar to her own with its windmills, canals, and main street with cafes, churches, taverns, and anxious townspeople watching the grim parade from their doors and windows, debating whether to stay or go.

Yet the faces of the townspeople were unfamiliar. No one called out a greeting or shouted her name. The butcher shop was where the baker should be. There was a school where the post office should be. She found the train station with the crowds of panicking people, suitcases everywhere, the trains full. Her throat was dry, and she took a drink of water from a canteen she’d packed, one of those relics from La Grande Guerre her brothers had plowed up and that now actually was useful. She knew little of geography, but she knew Marseille was a long way away and that somewhere, somehow, she would have to find a train to take her there.

She got back on her bicycle, pedaling away from this village and toward the next, the road thick with refugees. She did her best to maneuver through them, dodging people and random things. A pot, a shoe, a toy drum, a bicycle with a flat tire. Farther up, two deep ditches ran along each side of the road, making it impossible to pass. There were now so many refugees, at times, there was not enough room to ride, and in places she got off the bicycle and walked. Adding to the congestion were cars that had broken down or run out of gasoline. Other items that had become too burdensome were left where they fell. A green velvet sofa with long yellow fringe. A straw mattress. The tallest birdcage she’d ever seen, colorful finches flitting around inside.

Another hour of traveling passed, all countryside, not another village. She came to a crowd gathered in a field along train tracks. A train was stopped, and as she got closer, she saw it was a circus train. On the open fields, elephants linked trunks and tails. Horses grazed in the grass with their trainers. Acrobats stretched. A monkey screeched at a lion in a cage, the cat’s face framed in a golden wreath of mane. There was a very fat woman and a very tall man and something else that was either a man or a woman, Annelle wasn’t sure which. She heard someone say the train’s engine had broken down. A line of people veered off the road, attracted to the strange sight, gawking at the animals and performers who sat on the ground smoking and cursing.

Annelle kept going. She’d just passed the circus when she heard a distant drone. The crowd in front of her slowed then suddenly came to a dead halt. The road was hopelessly clogged, as everyone looked up at the sky, that clear blue sky that went all the way to heaven. She shielded her eyes against the sun. Black dots in the distance grew larger. Around her, mouths fell open. Families clutched one another. Annelle realized the dots were planes moving steadily closer.

“It’s the Americans,” someone shouted.

“No, the British,” someone else said.

People started waving and calling out. The planes came in closer until they were flying so low it seemed they would land on the people in the road. That was when they could see the pilots, the black markings on the wings. There were screams, shouts to take cover. The planes were over the circus when she heard a staccato sound, like the sound of her knife chopping on the cutting board, over and over, thump, thump, thump, at a rapid pace. She scrambled into the ditch along the side of the road. There were others there trying to bury themselves in the dirt. The German planes circled and came back. Annelle heard more screams, that staccato sound again and again, louder and then growing more and more distant until it was gone. The planes were gone, but a long time passed before she was ready to climb out of that ditch.

When she did, the first thing she saw was a horse on its side in the middle of the road, heavy and lifeless, a gaping hole in its flank. All around, there was moaning and shrieking. There were those who were able to climb out of the ditch, those who were not. Two little girls with white bows in their hair looked as if they were asleep but for the dark pools of blood staining their clothing. A woman in peasant clogs lay crumpled on the ground unmoving, a trickle of red trailing from the side of her mouth, her crying infant still in her arms. An old man lay on his back, his eyes open but no longer seeing, an expression of agony on his face.

She looked away, her stomach heaving from the sight and also from the knowledge that the Germans could do this, that they could fire bullets from planes on old men, women, and children trying only to escape. She understood now why so many had taken to the road, and she was worried about the sisters and what would happen to them when these German killers reached the convent.

She attempted to brush herself off, but the dress was torn and covered in filth that couldn’t be wiped away. There were people, survivors, working to clear the road, covering the dead in sheets or blankets. A young woman took up the crying infant. Annelle vowed to move faster, to get off the road as soon as she could, but when she found her bicycle near the ditch it was trampled, the frame twisted and bent. Tears stung the corners of her eyes. The bicycle was her wings. She thought of the finches in their cage. Why hadn’t anyone let them out?

She had to keep moving. There had to be a village nearby. The sun was setting. She tried to think of how long she’d been on the road. It seemed as if it was days, but it was just five hours, maybe six. At last she came to the next village, but the trains weren’t moving. The circus train blocked the tracks. She was alone, and soon it would be dark.

She saw people settling in to sleep in their cars or out in the open. All of the hotels, she heard, were either closed or full. She was too frightened to sleep, but her feet ached, her shoes rubbing skin raw in places, her body weak. She sat in the ditch along the road, clutching her knapsack with her brothers’ money to her, finishing the apple, the wedge of cheese, and almost all of the water in her canteen. Throughout the night there were voices—children crying, mothers soothing, whispers, a man’s strange, incomprehensible shrieking, the sound of footsteps—and she huddled into herself, praying for her soul, her safety, her brothers, and the sisters.

When the sun came up, she went out on the road again, moving along with everyone else toward the next town, listening for the drone of the planes, and, in places, she saw more evidence they’d left behind. More dead horses along with cows, mules, dogs. More dead travelers laid out in rows on the side of the road by Good Samaritans though there was no time to bury them. And chickens that had gotten loose in the melee, darting over the bodies with their spiny, pronged feet and pecking at them as if they were mounds of feed.

She passed mothers searching for lost children, clutching at people, thrusting photographs into their faces. She passed scraps of paper tacked to posts along the road, desperate scribbling asking for help finding lost sons and daughters and elderly family members. Jacques, five years old, wearing a blue shirt, last seen near Lille. Hanna, eight years old, yellow braids, a lazy eye, lost at Cambrai.

More rumors spread along the line of travelers.

“The Germans are in the next village!”

“The Americans are coming to save us!”

“England has surrendered! Hitler has moved into Buckingham Palace!”

There was talk too about the fate of the circus.

“The lion escaped from his cage. He’s the sole survivor.”

Annelle imagined the lion shaking his thick mane with an angry growl then turning and bounding off, searching, like everyone else, for a haven in the French countryside. But now there were thousands of Germans and one lion on the loose. There was no haven.

***

Another rumor—the Germans had cut straight across the country. They had separated the French army in the south from the British army to the north. And so the great mass of refugees, Annelle caught in the flood, turned north. They headed for the English Channel, away from Marseille, away from Francois and Philippe.

There were desperate people on the road. Looters. Thieves. Criminals ready to take advantage. Soldiers who had lost their regiments, who were not in their right minds. And hungry, panicked refugees.

The fruit and cheese Annelle had packed were gone. She refilled her canteen from a well in an abandoned yard. In the villages she passed, most of the cafes and stores were shuttered and closed. Words were scribbled in chalk on the closed doors of the boulangeries: no bread—useless to insist. She hadn’t eaten a real meal for two days. She didn’t remember the day or how long it had been since she’d left the convent. With the horrible sights she’d seen along the road, the constant terror, she hardly knew who she was. Her feet were raw and swollen.

I should have stayed at the convent, she thought, I should have never left.

She was ready to sit down on the side of the road and wait for the German planes to come and shoot their bullets at her when a convoy of British trucks passed. One of the lorries stopped, the soldiers taking pity on the refugees, hoisting those they could into the lorry bed, Annelle one of the lucky ones among them.

***

Outside Dunkirk, the convoy stopped at a checkpoint. From the bed of the lorry Annelle could hear a British officer, off to the side, talking to a group of soldiers.

“Uncanny, really,” he said. “A lion loose in the French countryside. Seems a traveling circus took a direct hit. Elephants, monkeys, acrobats, and what have you. Dead and dying. The lion tamer had gone down. No one else knew what to do. So I tracked the old boy like I would any other lion. Tracked it to a dairy farm. Found it eyeing a herd of cows. Seems a bomb had fallen in the middle of a pasture. Undetonated. The cows tongued it as if it were a giant salt lick. That lion was right there, eyeing them, waiting for the right moment to pounce. So I took aim, fired, and that was that. I now hold the record for shooting the most lions in the French countryside. One.”

Annelle wondered if she was dreaming the words he said or if they were real. The whole journey, the exodus of people, everything about it should have been a dream, but it wasn’t.

***

Dunkirk was an ugly town. There were factories and warehouses, and it smelled of rotting fish, burning oil, and smoke. They climbed out of the soldiers’ lorry. As soon as they did, the soldiers slashed the tires and hacked at the engine and other vital parts with the butts of their guns.

“What are you doing?” she asked, horrified.

One of the soldiers, whacking the lorry’s windshield with a tire iron, answered back, shouting over the shattering glass. “You wouldn’t have us leave all this for the enemy, would you?”

She looked around. Vandalized military trucks, cars, and tanks were everywhere.

In the town itself, thousands of British troops crowded the abandoned shops and cafes on the boardwalk, any place where they could take cover or where they might find food or cigarettes. A carousel and a Ferris wheel stood frozen in time, like relics from a golden age, great plumes of smoke floating to the sky in the distance behind them. Beyond the boardwalk was the sand and, after that, the Channel. She hated the ocean as soon as she saw it. Cold and gray, it stretched out farther than she could see, a great, fluid, impenetrable wall. British army trucks were driven out into the water and arranged in neat lines perpendicular to the shore. British soldiers climbed over them as makeshift piers to the deeper water where large naval ships waited to rescue them. She watched, a sick feeling in her stomach, anger rising.

The British army was leaving. In the dunes, some of them hid, their heads dotting the beach, their bodies buried beneath the sand, waiting for orders, waiting for their turn to go.

But the French civilians had no orders to wait for. They had no ships to take them to safety. They were trapped. Dunkirk was the end of the world, the end of France. She had no idea what to do next. The great swarming presence of all these lost men, the banging, hissing, and screeching of machinery being destroyed, disoriented her. A beached sailboat careened on the sand, its sail hanging from its tall mast in tatters. Groups of soldiers were scattered about the boardwalk and the sand, boxes of supplies piled all around, here and there vehicles with medical insignia. Discarded ration tins, bottles, and blood-soaked rags littered the beach. She reached for her rosary, forgetting she didn’t have a pocket or a rosary.

She was filthy, her dress in tatters. Crossing herself, she said a quick prayer for the sisters and her brothers and all the French soldiers fighting on alone now, without their British allies.

Annelle looked out at the ocean. Some of the ships were smoking, some were listing, the water filled with debris. A man’s body floated face down, moving in and out with the tide.

Someone grabbed her arm. “I have a hiding place,” a British soldier said. “Come with me.”

A hiding place. A safe place.

She was used to trusting people. His uniform was wet and caked with sand and mud. He smelled of manure, trash, and sweat, an odor indicative of his hiding place. There was something about his grip on her arm. There was something about the way he looked at her, his eyes unfocused and rimmed in red. She jerked away and ran, her feet burning with pain.

She ran straight to a small marina. Most of the slips were vacant. The few boats there were broken down looking, rusted out. An old sailor with black teeth and tattoos on his arms and fingers ushered civilian refugees onto a small, corroded barge. Annelle gathered her nerve and asked where he was going.

“Out of here,” he said, untying a rope. “Boat’s full.”

“Surely there’s room for one more,” she pleaded.

In the distance behind her, a loud explosion was followed by another. She felt the earth shift beneath her feet. She had to get on this boat, but the man ignored her, moving to the next rope, muttering to himself about a boat full of useless women and snot-nosed brats. There was a tattoo high on his right arm, a heart, inside it, a name in script: Sophie.

An idea struck her.

“Shame on you,” she said. “Leaving a woman alone to face the Germans. What would Sophie say?”

He looked at her. “Sophie?” he said. “Do you know—” He stopped himself and looked at his arm, shaking his head, muttering, “Merde.” He hesitated, kicked at a rope. “Just get on. Hurry, will you? What is the harm of one more useless woman?”

Annelle climbed aboard. He untied the last rope.

“Stay down,” he said, getting aboard himself. “Don’t touch anything.”

The deck was crowded with crates and refugees, women and children huddled together, exhausted and frightened. She searched for a spot to sit down and found an empty corner near the water. The boat pulled out to sea, rising and dipping with the waves, a strange sensation. In the distance, she saw the towering belfry of a church in the center of the city rising up out of the smoke, reminding her of the convent. Had the Germans reached it yet? Would they have mercy on the sisters? Her stomach turned. She glanced at the other passengers, dirty, frightened, hungry, like her. Overcome with nausea, she closed her eyes, not wanting to open them again until land was in sight. She had no idea where they were headed.

When she heard the familiar low hum, she opened her eyes and clutched her knapsack tightly to her chest. In the distance, planes headed toward the boat in formation, specks in the sky. Soon they were no longer specks. They were directly overhead, but there was no ditch to hide in, no sand to burrow into.

Some of the passengers screamed, some jumped overboard. Annelle clung to her knapsack as if it were Sister Marie Michel’s rosary. There was a loud explosion, a sharp, piercing pain in her ears, and then all sound went away. She could see, but not hear, a deafening sort of silence. She saw water and pieces of crates shoot up into the sky. She saw black smoke that she tasted in her throat. She felt herself cough, though she couldn’t even hear that. She felt the barge break away underneath her, the water pull her down, and how cold and slippery it was.

She saw others who had been on the barge bobbing in the water, floating away, or under. There was a white life preserver just out of reach and splintery pieces of crates and barge all around her, too. She flapped her arms and kicked her feet, swallowing water that made her choke, until she reached a long plank. She held on to it, able to throw her arms over the top and float, the sensation of ocean churning in all different directions around her, of more explosions and smoke, but it was all silent. There was no sound but the cries in her head.

***

Someone gripped her. She was hoisted up, out of the water, and put on her back. The sky was clear blue again, that Virgin Mary blue. Someone put a blanket over her. She felt her knapsack twisted around her arm. Ocean spray hit her face. Her head ached, and she was chilled, teeth chattering despite the blanket. She knew she was on a boat, a different boat.

“You’ll be all right,” a male voice with an English accent said. “Don’t worry. We’re almost ashore.”

Ashore.

She could hear again. Relief filled her, but she prayed he didn’t mean Dunkirk. She tried to sit up. Leaning on one elbow, she saw small cuts and scrapes all over her arms. Her shoes were gone. There was a deep gash on the sole of her foot.

The boat plowed ahead. Around it, vessels of all shapes and sizes were everywhere, all headed toward a distant wedge of land. When she saw the rocky coastline at first she thought it was Africa. She imagined sand dunes, turbans, a warming sun, and her brothers. But when the boat pulled into the harbor it wasn’t like that at all. There were soldiers all around coming off the boats from Dunkirk. And, in the harbor, women in uniform, clean and smart, leading them toward trains.

“Where am I?” she asked as she was helped on to dry land.

“England.”

© 2017 by Judithe Little

Ann Weisgarber:

“Beautifully written and rich with atmosphere…a stellar achievement.” ~ Ann Welsgarber, author of The Personal History of Rachel Dupree and The Promise.

Forward Review:

“…a riveting and enlightening mix of history and fiction that puts a human face on the costs of war…engaging…” ~ Foreword Reviews

Book Perfume:

“…the more I read, the more engrossed I became in their lives and relationships. Churchill, the secondary characters, and even the Hall itself are all served up with flourish, creating the kind of atmosphere you can get lost in for hours. I’ve read a lot of fiction set in this era, but this was the first book I’ve read that explores the heart-wrenching circumstances that brought ally against ally in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir…If you love history, beautifully rendered characters, and stories that will tug at your heart, add Wickwythe Hall to your list. It’s a striking first novel…” ~ Book Perfume READ FULL REVIEW

Alina’s Reading Corner:

“A Beautiful story of friendship, love, and loyalty during a wartime. My rating: 5 Stars.” ~ Alina of Alina’s Reading Corner READ FULL REVIEW

Historical Novel Society:

“The author has skillfully brought these three fictional characters together at Wickwythe Hall, and the story develops from there. The first chapters left me with the impression that this book would be a light romantic WWII read. But as I read on, it had substance with endearing characters and solemn subjects. It is based on the true events of WWII Operation Catapult, when Churchill made the decision to bomb the French naval fleet at Mers-el-Kébir to prevent their battle ships being handed over to Germany. Little’s characterization of Churchill is so well done. She makes his personality and presence so real. Mabry was a character to be admired for her decisions and actions. A good read with a satisfying ending.” ~ Historical Novel Society READ FULL REVIEW