BY: A. J. SIDRANSKY

BY: A. J. SIDRANSKY

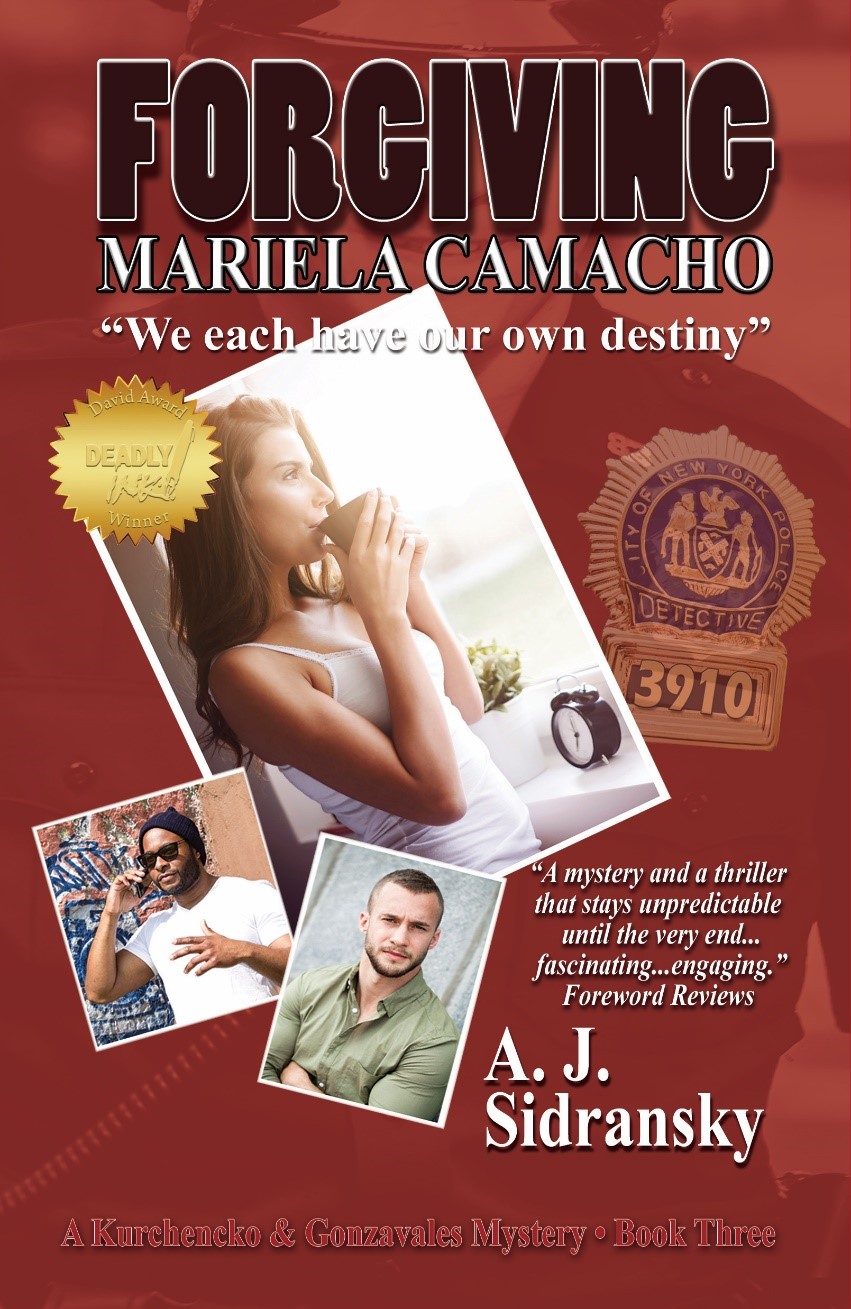

Pete Gonzalvez knew from the start that the dead woman he and his partner, Tolya Kurchenko, discovered in a Manhattan apartment did not commit suicide. Pete knew her better than that. Mariela Comacho was the love of his life. The road to the truth winds through the slums of the Dominican Republic, the cold streets of Soviet Moscow, the hot sands of the Judean Hills, and into the dark clubs of New York City’s underworld. They learn that Mariela was not merely murdered but was the most recent victim of an international serial killer—a phantom from Tolya’s past—and Karin Kurchenko, nine months pregnant, could be in his cold-blooded crosshairs.

Forgiving Mariela Comacho, the third book in the Forgiving series, is A. J. Sidransky at his best. A fast-paced thriller with witty, gritty dialogue and thoughtful perspective, its pages are rich with the engaging elements that continue to draw readers to Sidransky’s unique prose.

© 2021 by A.J. Sidransky

“This page-turner is more than a first-rate mystery. It explores family bonds and dysfunctional relationships, Jewish identity, and the intimate connection that develops between police partners. Mystery readers will greatly enjoy this novel, but it will also appeal to all readers looking for new and insightful explorations of Jewish identity, intermarriage, and parenting.”

—Jewish Book Council

“Streetwise, savvy and smart, Forgiving Mariela Camacho is an engrossing and intelligent read that takes the reader on a global manhunt that brims with noise, energy and authenticity. It feels real. It is both remarkably sweeping and intimate, simultaneously. Sidransky deftly creates narratives, characters and dialogue that exude genuineness and are a testament to his prodigious powers of cultural observation and storytelling. Forgiving Mariela Camacho is a worthy follow up from an author who weaves tales that practically pulsate with grit, gravitas and intensity. Can’t wait to read what he conjures up next…”

—Led Black, Uptown Collective

“I remember thinking as I closed the covers of the previous book in the series, “Forgiving Maximo Rothman” that Sidransky was going to have a tough time topping it…but he has managed to do just that!”

—Amos Lassen Reviews

PROLOGUE

Washington Heights, NYC

1 June 2010

9:55 p.m.

Mariela felt the steel blade slide across her neck. It didn’t hurt, not at all. That made her smile. She liked that her face would look forever happy. The coldness of the blade was what struck her. A knife never felt like that in one’s hand. Then she felt wet and realized it was her blood, warm against the place where she’d felt the cold knife. It dripped down her neck, then reached her T-shirt, producing yet another sensation, a thick stickiness between her skin and the fabric. She wanted to sigh but couldn’t.

She opened her eyes and looked around the room, realizing this was the last thing she would ever see. How sad, so far from the place she thought of as home, and the people she loved. In the corner of the room, on top of the ebony dresser, was a framed photograph of her daughter. Love welled up in her. She had done this for her and thanked God she was safe, far away from here. Her eyes closed slowly. She saw only blackness. The blade finished its job and, before she realized it, this world had slipped away.

CHAPTER 1

Washington Heights, NYC

3 June 2010

4:15 p.m.

Tolya was looking at the clock when the call came. He was a wreck these days. One would think that with the impending birth of his third child, he would be an old hand at waiting for the call. But every time the phone rang he thought it was Karin. He knew that in itself was ridiculous. He was a detective with the New York City Police Department. There were a hundred reasons his phone would ring for something other than his wife calling him to tell him to meet her at Columbia Presbyterian. Nevertheless, he was nervous, more so than usual. This pregnancy had not gone as smoothly as the previous two. The doctor had said the baby might come early, so though she wasn’t due for another six weeks, Tolya was certain little Oleg was on his way and that every call was that call from Karin.

He stared at the phone for two rings before he heard Pete from behind him. “You gonna pick that up?”

Tolya reached over the desk and grabbed the phone. “Detective Kurchenko,” he said into the mouthpiece.

“You’re up. Front and center with Gonzalvez, now,” the duty officer said, then hung up before he could say okay.

Tolya was relieved. “Pete, come on,” he said, taking his cell from atop the desk. He knelt and pulled open his bottom drawer and withdrew his gun, slipping it into the holster under his pant leg in one swift motion before turning for the door.

“Finally,” Pete said. “It’s been a slow day.”

Tolya smiled. “For who?”

The super was waiting at the front door of the apartment building on Wadsworth Avenue between 190th and 191st streets. Tolya chuckled to himself. What real estate genius built a luxury apartment building in this location? He had read about it in the Manhattan Times, the neighborhood’s free bilingual paper. The building had been conceived as a condominium before the market collapsed in 2008. The builder had been forced to rent the units rather than walk away from the building. At least there would be an elevator.

“You speak English?” Tolya asked the super.

“No,” he replied.

“All yours.”

“What’s the story?” Pete asked in Spanish.

“There’s a terrible odor coming from apartment 7-F,” the super replied. “The other tenants are complaining.”

“Who lives there?” Pete asked.

“A woman,” the super said.

“Did you try to get in?”

“Yeah, but no one answers, and the chain lock is against the door. I didn’t want to break it.”

“So, you called us.” Pete sighed and explained to Tolya what the super had said.

“Okay then, let’s go up and break in.”

Pete grinned. “I was hoping you’d say that.”

The smell in the hallway was overwhelming. Tolya knew what it was before they unlocked the door. Only a dead body smelled like that, and then only after a few days, and the last few had been warm.

He slipped his hand into the crack between the door and the frame, realizing immediately that there was no way his large mitts could unhinge the lock. He knew Pete’s hands were even bigger than his. “Anyone there?” he called out. “Police.”

There was no answer, though the neighbor from across the hall had opened her door. A small woman in a blue and red bathrobe with her hair in curlers stepped out into the hallway, a handkerchief over her mouth and nose. “I told him to call you yesterday,” she said.

“Thank you, ma’am,” Pete replied, smiling. “Now please go back into your apartment and let us do our job.” He turned back toward Tolya. “What do you wanna do?”

“Shoulders, I think,” Tolya said. Simultaneously, he and Pete rammed the door with their bodies, shoulders first. It took three attempts, but the chain did give way and, as the door opened, the smell intensified.

Light streamed into the apartment, the late-afternoon sun blazing through the uncovered windows. They were blinded at first. “Police,” Tolya shouted out again. Still no response. Both he and Pete pulled their guns. As Tolya turned to Pete to tell him he would lead, he saw the super cross himself and withdraw from the apartment.

They walked slowly down the narrow hallway into a small foyer that opened into a large living room. What they saw was inconceivable to both. In front of the window, silhouetted against the sun in the western sky, was a huge wooden frame. Suspended in the frame was a woman seated in a chair, her hands extended like Jesus on the cross. A kitchen knife dangled from her right wrist by a leather cord. Her body slumped forward. By the volume of blood that covered her, it was obvious that her throat had been cut.

Tolya and Pete pulled handkerchiefs from their pockets and covered their mouths and noses. “Check the rest of the apartment,” Tolya said through the handkerchief, lowering his gun. As Pete moved out of sight, Tolya moved toward the victim. He removed a pair of latex gloves from his back pocket and slipped them on, then gently lifted her head. Her face was contorted into a smile. Despite the heat, he shivered.

“All clear,” Pete called out, coming back into the room. He walked toward Tolya and the dead woman, then stopped in his tracks. His eyes widened and his mouth opened, but at first nothing came out. He vomited and collapsed to his knees. Pete looked up at Tolya. “I know her,” he said before passing out.

![]()

Karin cleared the last of her papers off her desk filing them in the appropriate folders in the cabinet behind her. She had been messy all her life, but this job changed that. Managing museum exhibitions required more organization and neatness than police work had, at least on top of the desk.

She was particularly excited about this exhibition, as it was her first as a full-time employee of the Museum of Jewish Heritage. She had worked on it as a volunteer before she had decided to go back to work full time. She didn’t want to go back to her job at NYPD Internal Affairs. She had been volunteering at the museum when a permanent position opened. She applied, despite her lack of experience in museum management. It turned out her Spanish skills, coupled with her personal connection to the few living survivors of the Sosúa experiment, were more important than a fancy graduate degree. “Dominican Haven,” an exhibition dedicated to the 854 Jewish refugees saved by the Dominican Republic during WWII, was set to open in a couple of weeks. She would be there, pregnant or otherwise, unless she was actually giving birth.

She looked at the clock, 5:15. She was already late for their class. She had hoped that she and Tolya would finish their conversion course before the new baby came, but if Oleg came early, well, some things were beyond her control. She stopped and texted Rabbi Rothman to tell him she would be a little late, then turned on the small TV on her wall. She wanted to check the traffic before heading uptown. Tolya had insisted she begin driving to work a few weeks earlier. He didn’t want her going into labor on the subway. The museum gladly supplied her with a parking space rather than lose her earlier than expected, especially with the show opening.

“Breaking News” flashed across the screen as it popped to life. She read the caption: “Unidentified woman found dead in locked apartment in Washington Heights.” She recognized the curve in Wadsworth Avenue, then saw Tolya’s face. Karin sat down at her desk, pulled out her phone, and texted him, “What happened?”

Seconds later, she saw him reach into his pocket and check his phone. Then, seconds after that, her phone vibrated. “You wouldn’t believe what we found. Tell you later. Can’t make class. Please tell Shalom.”

“Okay,” she texted back, then she called the babysitter and asked her to stay for an extra hour.

Pete sat dazed in the interrogation room at the precinct. Tolya and the captain sat opposite him. “Pete, tell us again, how you knew her?” Tolya said.

“I helped her come here,” Pete said.

“Is she related to you?” Tolya asked.

“Not really. Sort of, a cousin, kinda,” Pete replied, then thought for a moment. “She was the cousin of my cousin.”

“How long has it been since you’ve seen her?” the captain asked.

“About ten years.”

“Yet, you recognized her?” the captain said.

Pete’s mind raced back. He couldn’t forget passion like that. “Yes,” he said, nodding slightly.

“What was her name again?” the captain asked.

Pete swallowed hard. “Mariela Camacho.”

“The woman’s ID—or should I say, one of them, anyway—confirmed that,” Tolya said. He took a plastic baggie with a Dominican passport out of a file and dropped it onto the table.

“How many did she have?” the captain asked, removing the Dominican passport from the bag and flipping through it.

“Three,” Tolya said. “One Dominican, one American and, get this, one Russian.”

Pete shook his head. He couldn’t believe what was happening. He’d been a cop a long time, but never had he expected to find a dead body—no, a mutilated dead body—of someone he knew at a crime scene. “I just can’t digest this,” he said.

“I understand,” said the captain. “Maybe we should pick this up tomorrow. You can write out a statement, tell us what you knew of her. And I’ll have to take you off the case.”

“Of course,” said Pete. He rubbed his shoulder where he had hit the heavy front door of the apartment earlier. “Tomorrow. That would be better. I can’t do this now.”

They all rose to leave. The captain walked around the table and put his arm around Pete, the ever-increasing bulk of his stomach pushing Pete into the corner of the tiny room. “Gonzalvez,” he said, “I’m sorry about this. Go home, kiss your wife and kids, and get some rest. We’ll sort this out.”

“Thanks, Cap,” Pete said, then looked at Tolya. He knew Tolya understood to hang back for a moment after the captain left. As the captain walked through the door and down the hallway, Tolya turned to Pete. “What’s up, hermano?” he asked.

“Let’s go get a drink. I need to tell you a few things.”

“Sure,” replied Tolya. “I already told Karin I’d be late.”

![]()

Karin walked quickly up the steps of the Yeshiva on Bennett Avenue. Once in the vestibule, she made a quick left and headed up the stairs, holding the banister with one hand, the other under her pregnant belly, supporting herself. She loved being pregnant but hated the last trimester. She was big and felt uncomfortable in her own body, like she took up too much space. She also couldn’t wait for the little life inside her to wrap himself around her neck and breathe in her ear. She reached the second floor and stopped for a moment to steady herself then walked to Rabbi Rothman’s study at the end of the hall.

She liked Rothman. He was a good and honest man and, although she knew she would never practice his severe, rigid, brand of Judaism, both she and Tolya felt comfortable having him complete their conversions. Tolya, though, had bristled at the idea that he needed to be converted at all.

He was the genuine article, Rothman, a man who had come to his faith by choice rather than just acceptance. She knew his beliefs were a matter of conviction, not indoctrination. Also, she respected how he had embraced a friendship with Tolya, a friendship that had changed Tolya deeply after Tolya had arrested Rothman’s wife for murdering Rothman’s father. She admired his dignity, a quality she rarely found in people.

Karin knocked gently on Rothman’s door, the old sign with his father-in-law’s name still appended to it. He had died a broken man a few months earlier, never recovering from the tragedy of his daughter’s actions.

“Come in.”

She opened the door slowly and peeked in. “Good evening, Rabbi,” she said. “Sorry for my lateness.”

“Not a problem, Chava,” Rothman said, using the Hebrew name she would soon adopt as her own. Chava, Eve, the first woman, the mother of mothers. “Where is Akiva?” Tolya picked that name because it had been his maternal grandfather’s Hebrew name. As far as Tolya knew, he was the last member of the family who had had one. Tolya and his twin, Oleg, had been close to him as children, spending summers with him and their grandmother in Ukraine.

“He’s caught up on a case, up on Wadsworth,” she said, settling into the chair opposite Rothman’s. “He asked me to send his apologies.”

“Hmm,” replied the rabbi. “I saw something earlier on the news. Seems it was a rather grisly scene.”

“Yes.”

“Well, let’s get started then. Do you have any questions about what we discussed last week?”

Karin paused for a moment in thought. She did have questions, but she wasn’t sure how to ask them. “Yes,” she finally said.

“Then why are you hesitating?” said Rothman.

“Because I don’t want to offend you,” she replied.

Rothman leaned back in his chair and smiled. “Karin, nothing you say will offend me.”

“Even if it offends the rules you live by?”

“You know me better than that. My rules are for me,” he replied. “You may choose to live any way you want. I can only hope to guide you. What happens between you and HaShem is your business.”

“Well, then,” Karin said, shifting herself slowly into the chair to relieve the pressure against her back. “I understand thoroughly the idea of rest on Shabbat, of separating the holy from the profane, but I can tell you with all honesty that we, my family, Tolya and me and the kids, we won’t observe the Sabbath in the way you do. It’s not practical for us. Yet, I want to build a construct within which my family will experience the Sabbath.”

The rabbi smiled at her and placed his hands on the desk. “Chava,” he said, “I am going to tell you a little story. But if you ever tell anyone I told you this story, I will deny it because, as a rabbi of such a traditional congregation, I would be run out of town for suggesting this to you.”

“Go ahead.” Karin laughed. “It’s our little secret.”

“Many years ago, before I became ba’al t’shuvah, I was going on my first trip to Israel and I had a pair of tefillin that had belonged to my father’s grandfather. My father had carried them with him from Europe. I wanted to pray with them at the Western Wall in Jerusalem. You understand what tefillin are?”

“Yes,” Karin answered. “The small boxes men wrap around their arms and forehead when praying. They contain a passage from the Torah.”

“Very good.” Rothman gave a broad smile. “I’ve successfully taught you something. Anyway, I had to have the tefillin checked to make sure the parchments inside the old boxes were still good. There was one shop on the Lower East Side where you could do this. I went to the shop and found a very old man with a very long beard and a yarmulke way too big for his head sitting on a low stool repairing religious articles. There was another man in the shop as well, not quite so old. When I walked in I explained to the old man what I was seeking—to make certain that the tefillin were kosher—and before the old man answered me, the other man chided me for coming into the shop with my head uncovered. The old man, who had been silent till then, turned to the other man and told him to apologize to me for his rudeness. He said that, though I didn’t wear a yarmulke on my head, it was clear I was wearing one in my heart.”

Karin shifted again in the chair, then smiled. “So, Rabbi,” she said, “are you suggesting that I can build a construct for Shabbat that might differ from the more traditional approach?”

“I have a very intuitive student,” he replied.

“And I a very tolerant teacher.”

“What are your plans for your first Shabbat?”

“I plan to have a family dinner where we will bless the wine, the challah, and the children, and then for us to spend the evening together with the kids, no television. I have a special project planned for Tolya and the boys to do together.”

“Excellent. Good luck with it. And let’s talk again early next week.”

Karin got up slowly from the chair. Shalom came around the desk to help her. “Chava,” he said, “a question.”

“Yes, Shalom, what?”

“Are you sure you want to do this?”

“Do what?”

“Convert.”

“Yes. Why are you asking me that now?”

“We have an old custom that we must continue to ask at least three times before the conversion is undertaken to make sure the person’s heart and mind are together in the decision.”

“They are.”

“And why are you doing this?”

“I want my children to understand this part of who they are, and, at the same time, I want to be able to share this heritage with them. I can’t do that if I don’t become a part of it.”

“And you accept, or should I say, you believe in our view of HaShem?”

“I believe there can be more than one interpretation of the same thing, and I am comfortable accepting this interpretation.”

Shalom smiled. “Are you still planning on doing your conversion before the birth?”

“If possible, yes. The day after the pre-opening party.”

Shalom raised an eyebrow. “And will Tolya be joining you?”

She smiled. “I’m not supposed to tell you, he wanted to tell you himself. But, yes. He decided you were right, that he should look at this more as a recommitment than an insult to his personal history.”

Shalom smiled.

![]()

Pete downed the shot of Tequila without flinching, took a long swig of the beer and turned to the bartender. “Another, please.”

“You sure that’s a good idea?” Tolya said, sipping at his beer. “You’ve had three already.”

“I’m fine, Tol. You might want to consider having a couple yourself, before I tell you this story.”

“I’m fine with the beer, thanks. You ready to enlighten me?”

“I will be in a moment,” Pete replied. “Just let the tequila settle in a little first.”

He picked up the fourth shot and downed it. The warmth of the liquor rose up from his stomach into his chest. The effect of the first three began to lighten his mind. The rush of the tequila reminded him of the warm breezes coming off the ocean in Samaná that summer, all those years ago. The tiny fishing village, the broad beach lined with palm trees, the cozy room facing the ocean where they spent four days sleeping under mosquito nets, the windows open to catch the breeze and the sound of the surf. He looked Tolya directly in the eye. “Okay,” he said. “Let’s get right down to it. We were lovers.”

Tolya put the bottle of Corona down on the bar. He hesitated for a moment then said, “I can’t say I’m surprised.”

Pete turned his head away. They were closer than brothers, but sometimes Tolya didn’t know when to keep his comments to himself. Pete forgave him for that. He swallowed hard, remembering those moments so many years ago when he knew this woman, this woman who was now lying on a slab in the morgue at the coroner’s office.

“Wait, I thought you said you were cousins,” Tolya said.

Pete turned back toward Tolya. “I said we were cousins of cousins. No blood relation. But then, I don’t suppose you Russians ever marry within the family. Let’s see, didn’t that neighbor of yours end up marrying…”

“Okay, Okay,” Tolya replied, putting up his hands in surrender. “Point taken. Sorry. I shouldn’t have said that.”

“Enough said. Now, you wanna hear the story?”

“Yeah. And please, tell me everything.”

Pete lifted the bottle of beer, took one more swig then began. “It was my first time back in Santo Domingo in about six, seven years. I had just become a citizen and finished school. I wanted to take a little break before I began on the force. I was going with Glynnis, but she was still in school, so I went back to visit my family, my cousins, aunts, uncles, alone. It started out as innocent as could be.”