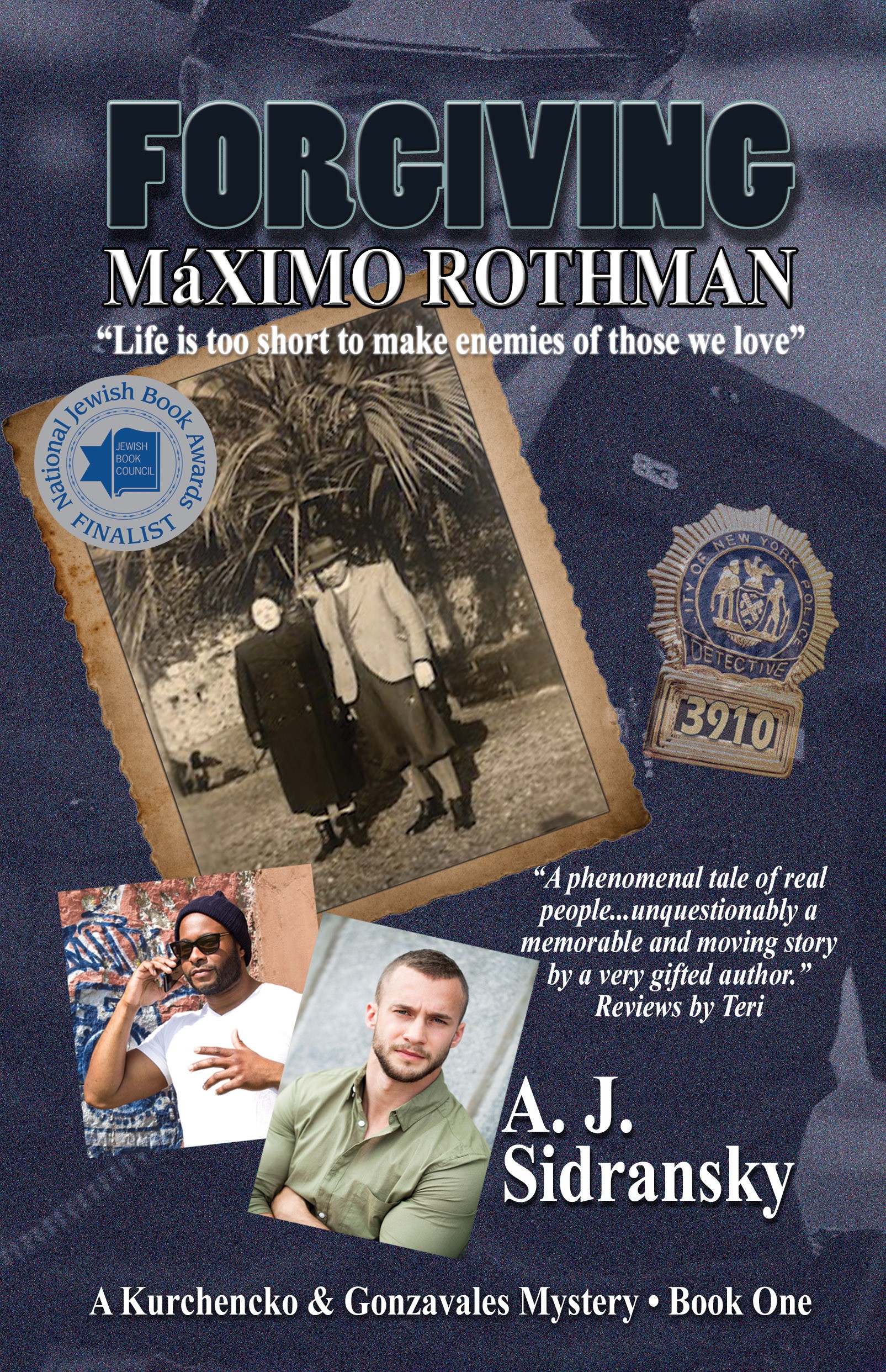

BY: A. J. SIDRANSKY

BY: A. J. SIDRANSKY

On a chilly autumn night in New York, the lives of two men born decades and continents apart collide when Max Redmond is found bludgeoned in his Washington Heights apartment. While investigating the crime, Detective Tolya Kurchenko comes across the dead man’s diaries, written by Redmond over four decades. He hopes the diaries will lead him to the killer. In fact, they help him sort out the complexities of his own identity.

Spanning 65 years and three continents—from Hitler’s Europe to the decaying Soviet Empire of the 1970s, and revealing the little-known history of Sosúa, a Jewish settlement in the jungles of the Dominican Republic—A.J. Sidransky’s debut novel leads us into worlds long gone, and the lives of people still touched by those memories.

CHAPTER 1

Washington Heights, NYC

25 October 2005

5:55 p.m.

María Leguenza walked briskly down Bennett Avenue, wrapping her brown cloth coat a little tighter against the chill in the autumn air. At 65, she was not as spry as she had been when she arrived in New York twenty years earlier. Men and women in somber dress rushed past her on either side. Tassels, dangling from the men’s clothing, flew in their wake. The women, holding onto their wigs, dragged their straggling children while trying to keep up with the men.

Maria pulled the keys out of her bag at 105 Bennett Ave. The shiny new security doors proved difficult to maneuver. Juggling her pocketbook and her shopping bags, she opened the interior door to the lobby nearly dropping the special treats she had brought for Señor Max: ripe plantains for maduros, pork chuletas and peppers, and a big slice of tres leches cake. She held the cake’s plastic container tightly so the creamy liquid inside wouldn’t spill.

Exhausted from the awkwardness of her arrival, she placed her packages on Señor Max’s welcome mat and inserted her key into the top lock. She left her packages by the door and flicked a switch to light the hallway in front of her. “Señor Max,” she called out. “Buenos tardes, estoy aquí.”

There was no answer.

“Señor Max, dónde estás?” María called out a second time. Still no answer. “Señor Max?” She felt a tightness in the pit of her stomach. Her heart began to race. He was old, very old.

She walked down the hallway toward the dark bedroom. The rubber soles of her shoes squeaked against the wood floor. Perhaps he was sleeping? She turned on the light. He wasn’t in the bed. It was unmade. Her heart now pounded in her chest. Turning back toward the bathroom, she noticed the light under the door. As she opened it, the bright light from the fixture over the sink bounced off the white tile walls, momentarily blinding her. She blinked. Then saw him.

![]()

In the brightly lit vestibule of the synagogue on Bennett Avenue, Rachel Rothman’s deft hands attempted to help her son remove his coat. “Baruch, my darling, help me help you,” she said as he fought her attempts. Though he was seventeen, he was as difficult as a small child.

“Zay,” Baruch kept repeating, struggling with the Yiddish word for grandfather. He pointed toward the heavy wooden doors of the synagogue each time they opened, making Rachel’s efforts all the more difficult and nearly knocking her over, her slight frame no match for his long arms. She had to stop and respond to each “Good yom tov” she received from arriving congregants. “Yes, Zayde lives across the street,” she replied with infinite patience acquired over years of disappointment.

“Zay,” he repeated again, “Zay.”

“Perhaps later, darling. Right now, it’s yom tov, we need to daven.” She felt a hand on her shoulder and turned her head.

“Rachel.” It was Shalom from behind her. “He isn’t ready yet? The service has begun, I have to go in.”

“Just one more minute,” she said, tugging at the black material, struggling to free up Baruch’s extended arm.

“Then you take him upstairs with you,” Shalom said, turning toward the sanctuary doors.

“You know I can’t do that anymore,” Rachel said, finally pulling the arm of Baruch’s coat free. “He’s too old to sit with the women. You have to wait a moment.”

“HaShem doesn’t wait,” Shalom replied, adjusting the wide brim of his hat.

“Yes, He does.” She straightened her dress, the gray flannel fabric smooth under her fingers.

Shalom took Baruch by the hand and led him into the sanctuary. He found two empty seats in the middle of a pew a few rows up from the back of the room. The service was in full swing, the congregants deeply focused on their prayers.

Shalom chanted with the congregation in near ecstasy. He loved the sound of the prayers: the timeless phrases floating up to HaShem, a supplication from his people, a plea for attention, for connection. Baruch stood to his left, nearly as tall, his beard finally growing in, though still scraggly in spots. He swayed along with his father, mimicking as Shalom had shown him. Shalom searched Baruch’s face as he prayed. He saw the same blank expression as always. He wondered if the words had meaning to Baruch. Did his son know HaShem?

The voice of the congregation swelled as the men began dancing with the Torahs. They carried them down the aisle—the blue-, red-, and green-velvet covers brilliant and shiny—out through the doors and into the street to dance with them in celebration. Shalom took Baruch’s hand and led him out into the street to watch. As the men chanted and whirled, their fringes flying wildly in the cold night air, a scream came from the building across the street.

![]()

María grabbed the towel rack with one hand and muffled another shriek with the other. She saw the blood from Señor Max’s head pooling slowly on the white tile floor. She backed out of the bathroom and began to cry. After a long moment, she steadied herself and looked back into the bathroom. She thought she saw Señor Max’s body move slightly, as if he might still be breathing. She ran into the bedroom and grabbed the phone.

“Nine-one-one. What’s your emergency?”

“Señor Max, he is on the floor in the bathroom…” She peeked into the bathroom, glimpsed blood and turned away.

“Is he breathing, ma’am?”

“I don’t know.” Her heart beat hard in her chest. “Dios mío, ayudame.”

“Ma’am, can you go over to him and see if he’s breathing?”

“No, no, I can’t to go back in there. You just send the doctor, please. Hurry please, ay Dios.”

“Okay ma’am calm down. What unit are you in?”

“One-O-Five Bennett, 6C. Please, hurry, please.”

![]()

Detective Anatoly Kurchenko stepped out of the elevator onto the sixth floor of 105 Bennett Ave. He looked around. He had been in this building many times over the years. His family had moved to Washington Heights in the late 1970s. He’d had a girlfriend who lived on the third floor. The walls were still painted that same shade of beige. The dull lighting made the hallway appear even dingier than he remembered. He saw the stretcher at the end of the hall.

“You don’t have a sheet over him, so I’ll assume he’s alive,” he said to the paramedic. Whenever he was nervous his slight Russian accent peeked through his otherwise solid New Yorkese. And he was always a little nervous at the start of a case.

“Yeah, he’s alive, but barely,” the paramedic said.

He looked down at the old man. An oxygen mask covered the lower part of his face: the rest of his face was bloodied and raw. “Anybody see anything?” he asked.

“I dunno, Tolya. The old woman inside called it in,” the paramedic answered. “Ask her.”

“The wife?”

“No. Might be the maid,” he said, pushing the stretcher toward the elevator. “She found him.”

Tolya opened the door slowly. He noticed the mezuzah on the doorpost. He scanned the foyer for any telltale signs of forced entry or struggle.

In the living room sat two uniformed officers with an mature Hispanic woman on a high-backed, aging velvet couch. “Evening officers,” Kurchenko said, taking the two steps into the sunken living room in one stride.

“Evening detective,” both uniforms said.

“Is the evidence team here yet?”

One of the detectives pointed to the bathroom. Tolya saw a leg jutting out of the doorway, the strobe from the camera flash pulsating every few seconds. “Looks tight in there,” he said. “Let me speak with the nice señora.” He sat down on the sofa. “May I ask you some questions, Señora…?”

“Leguenza, but you just call me María, everybody just call me María.” She looked up at him.

“Thank you, María.”

“I found him just laying there, the señor,” she said before Tolya could get his first question out of his mouth. “Just laying there. It was terrible.”

“Yes, I’m sure it was terrible,” he replied, “but I need to ask you a few…”

“Dios mío,” she continued. “Who would do such a thing to Señor Redmond? He is a fine man.”

“Yes, I’m sure,” Tolya said. “That’s why we need your help, so please let me ask you some questions.”

“Okay, Okay, sorry,” she said, beginning to cry.

Tolya looked around the room while María composed herself. It was a study in drab. Faded furniture and yellowed curtains. “Was the door locked when you arrived?” Tolya asked.

“Yes, like I told the woman policeman, the door is locked. Everything was like normal, except Señor Redmond is on the floor in the bathroom.”

“What time did you arrive?”

“A qué hora llegué?” María mumbled, touching her fingers to her forehead. “I think it was about 6:10. I was supposed to be here at 6:00, but I want to buy Señor Redmond something special because it is their holiday tonight.”

“Yes, I know,” Tolya said. “We couldn’t get through the crowd.”

“So, I go to the bakery first to buy tres leches, he love tres leches,” María said.

Tolya stifled a smile. The idea of an old Jewish guy who likes tres leches cake was sweet to him.

“Ay dios,” cried María. The crying returned to weeping.

Tolya knew there was no benefit in continuing the questioning at this point. The woman was too upset. “María,” he said, “I need to ask you one more thing right now.”

“I’m so sorry sir,” she said through her sobs. “I too upset to talk.”

“I need to know who to contact. Does Señor Redmond have any family?”

“Yes, yes,” she said, her crying subsiding momentarily. “He have one son. His name is Steven Redmond. I get you his information.”

María rose from the sofa and went to the drawer in the center of the large mahogany desk against the back wall of the living room. She wiped her face with a lace handkerchief she took from her pocket, then absentmindedly slipped it into the cuff of her sleeve at her wrist. She took an envelope from the desk and handed it to Tolya.

He examined the envelope, “emergency” written in neat script across the front. Inside was a single sheet of white paper. “This is his son’s name and number?” he asked.

“Yes,” María said. “But he won’t answer the phone now because of the holiday. He is very religious.”

Tolya smiled. Another victim of superstition caught in a time warp.

“But if you go downstairs to la sinagoga and ask for him there, you find him now,” María said, interrupting his thought.

“Steven Redmond, right?” Tolya said looking at the name on the piece of paper again, turning it over in his hands as if expecting something else to magically appear.

“Yes, but at la sinagoga, ask for Shalom Rothman.”